“In my career spanning 30 years, I strongly believe that a person itself is an instrument of change and every person wants to do good and it is this potential for change and that kind of engagement is required to change women’s lives and the society for better.”

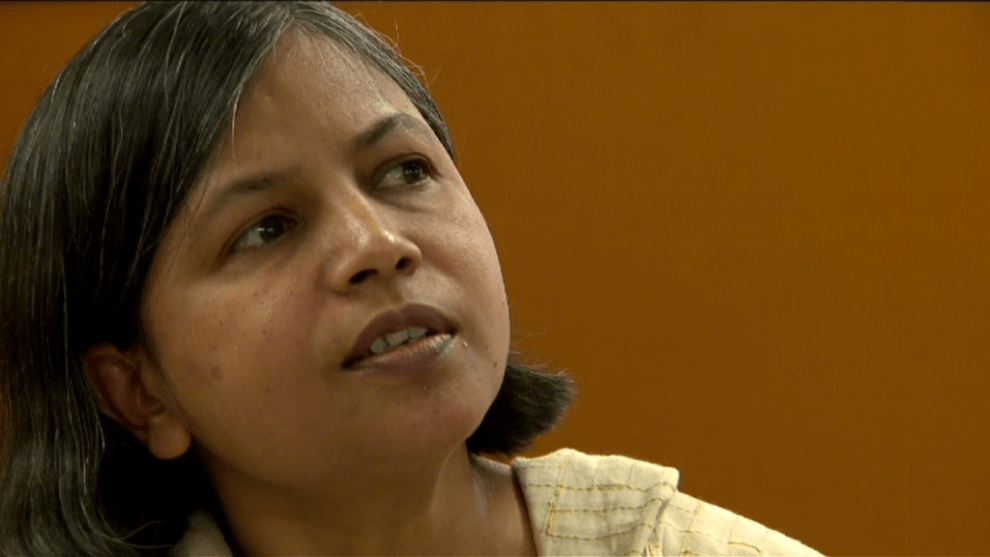

Madhu Khetan, Integrator,

PRADAN, India (madhukhetan@pradan.net)

Nimisha Mittal recently interviewed Madhu Khetan to explore Madhu’s experiences, achievements, and insights based on her three decades-long experience as a development practitioner with PRADAN. Excerpts from this interview.

What have been the unique characteristics of your journey with PRADAN as a person and as a professional? How did you get to know of PRADAN and when did you start working with it?

It was in August 1991 that I joined PRADAN. It’s been almost three decades since then. Looking back, it has been a journey of transformation of myself, personally as well as professionally. After graduating from IIM Lucknow, I joined the corporate sector and took up a job in Mumbai. After a couple of years in that profile, I met someone from PRADAN that led to my joining PRADAN. I was always interested in doing something impactful for society, especially for people who are more vulnerable and less fortunate. So, that’s how I landed up in PRADAN and went to work as an intern in a place called Godda which was a part of undivided Bihar then, and is now in Jharkhand. After spending two months there as an intern I decided that this is what I want to do and I joined PRADAN as a project executive.

SHG meeting in Godda

SHG meeting in Godda

How were your early years at PRADAN?

Internship at Godda was my first foray into rural India and everything was new in the sense of exposure to village life as well as to an NGO. I spent around six years in Godda and at that time, I was very curious to understand how groups worked. Even at that time PRADAN was offering opportunities for internships, which are two-three months and structured around some assignment, etc. There we were involved in creating an end-to-end intervention with communities on Tussar sericulture to broaden the people’s livelihood base. Apart from my involvement in the various facets of that programme, I was more intensively involved in initiating the women self-help groups (SHGs) which was just starting at that time. So, it took me a while really to understand the perspective and this was during 1991. While South India had many SHGs at that time – promoted by organizations like MYRADA – within PRADAN it was still early days. We had formed a couple of groups in Alwar in Rajasthan but beyond that there weren’t many such groups.

The poor have a strong dependence on informal credit mechanisms, in these kinds of low monetarized economies. At that time these groups were also called Mahila Mandals. So, it was also a place where women could come and have their own solidarity group, although that articulation came much later, I think. We also had an initial articulation of trying to improve women’s lives ‘mahilaon ko kuch sudhar bhi ho sake’. This helped in building SHGs and my own understanding about what SHGs and entitlement can mean to women also developed simultaneously. During my six years there we could increase the number of SHGs from seven to more than 300. We also did a lot of work in developing community cadres and promoting some aspects such as basic hygiene of groups, accounts, audit, bank linkages, etc. Around that time NABARD (National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development) had also come out with a pilot to link SHGs with banks. So, I spent a lot of my time with the community and banks to help with credit planning and in linking groups to banks.

With the Tussar sericulture programme, my involvement was more in the post-cocoon stage where women were involved in spinning and reeling activities. Women would come with lots of issues related to accessing entitlement, but not only restricted to accessing entitlement. I mean, for example, we used to provide women training on spinning and reeling under the Training of Rural Youth for Self-Employment (TRYSEM) programme. So, issues related to release of stipend were quite critical. So, all those issues such as how do you help women through documentation of their concerns and linking them directly to the public system became important.

I remember a village where there was a very intense fire which had gutted almost all the houses, so the issue there was related to accessing their entitlements (compensation) which the government announced after this kind of an incident. Even such issues were dealt with, though these were not really a part of the job description as PRADAN was very focused on the economic upliftment of communities at that time. But these types of interventions also gave me a lot of satisfaction at a personal level.

When did you move to Madhya Pradesh and start working on the Kesla project?

I shifted from Bihar to Madhya Pradesh in 1997. The shift was more driven by a need to be closer to home and also driven by the need to be in touch with a context that I could relate better with. In Godda I had been working with the Santhali communities where language was a barrier to really understanding women’s concerns. So, in 1997, I shifted to Kesla in Madhya Pradesh where I spent my next 10 years till 2007. Working at Kesla was a great learning experience for me as we were involved in facilitating and building higher tiers of women’s collective with the Narmada Mahila Sangh (NMS). Working with NMS helped me to learn about the various dimensions of political empowerment and

Women celebrating solidarity in an annual event

Women celebrating solidarity in an annual event

social empowerment. So that whole journey, I think, provided lots of learning for me as a development professional. And I think it has influenced the thinking within PRADAN around building women federations. There I was also closely observing the evolution of Kesla Poultry Society, and was also involved in other kinds of initiatives which were happening around land and water resource development and mulberry sericulture.

When did you move to Delhi and how have your roles evolved since then?

I moved to Delhi in 2007, and from 2007 to 2014, I was responsible for PRADAN’s work in Madhya Pradesh and I supported the six teams spread across southern and eastern Madhya Pradesh. From 2014 I am part of the central unit of PRADAN at the head office which integrates programmes and operations and undertakes Monitoring & Evaluation (M&E). Besides these, I am also involved with the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) interventions, mainly, influencing and providing technical support to NRLM on institution building, specifically on the 32,000 Cluster Level Federations (CLFs) that the NRLM has promoted across the country. Most of the work has happened around financial intermediation but not so much around building strong organizations or programmatic enrichment. So, this is an initiative to actually build a prototype on the ground across five states, but also build and strengthen the technical capacities of State Rural Livelihood Missions (SRLMs) across these states, and also working closely nationally with the NRLM at the central level. NRLM is looking at building these cluster-level federations as gender responsive institutions. That’s another significant initiative which I am currently involved with.

What has been your experience on working with women, and in the process integrating a gender perspective within programmes and building systems to address this within PRADAN?

We often talk of women’s empowerment and gender equality and many times synonymously or in the same breath. But, I think these are two very different concepts but it is not always very clear. Let me narrate an incident from a village in Kesla, Madhya Pradesh, to make this clearer. It was during the initial days, a time when all these groups were just beginning to take off. Early one morning, I reached a village to meet members of a group that was particularly very strong and proactive. Mornings were the best time to meet women as they would still be in their homes. I went around the village and meanwhile they were talking among themselves and also with me and talking about an incident that had happened the previous night in which one of the SHG members had been very brutally beaten up by her husband. She was apparently driven out of her house in the night and had spent the night in the forest. Thereafter, she was rescued and provided shelter by one of the group members. When the women actually sat down in the meeting, I was expecting to hear about that issue in the meeting but to my surprise they carried out business as usual – putting together savings, talking about the loans, etc. At the end of the meeting, I couldn’t stop myself from asking them whether they were going to discuss about this incident and what should be done. To this, they said; “nahi aap chinta mat karo” (no you don’t worry). Probably, they took my worry that this issue would hinder her work since she was a poultry producer also. This made me reflect that we assume that due to formation of a group, leading to solidarity of women who sit together and converse with each other it would automatically mean that they would respond to these problems. But strangely the response was that there was no response. Here I mean, there was no institutional response as a group to that member’s plight and I didn’t see the overlap happening.

We cannot really assume that because we are working with women that there is a gender angle in the work. So there has to be an intentionality on integrating a gender perspective within programmes. Once this kind of conversation started in PRADAN, then several colleagues shared their experiences. We heard of women buying assets by taking loans from the group but the asset would be in the man’s name. Extreme cases were from Chhattisgarh, of women taking loans so that their husband could get married a second time because she was not able to give birth to a boy. There were also day-to-day things that we all kind of accept – for example, women eating last in the family after everyone else has finished, etc. So that brought us to an understanding that there has to be an intentionality of working on these issues, and trying to address these because we are all (women as well as men) a part of the same society wherein this kind of thinking is embedded in both sexes and it is detrimental to both.

I have been fortunate enough to have been a part of a small group which was able to work on this agenda of actually bringing it to the attention of the organization, and to be involved in a pilot which looked at systematically integrating gender perspectives within women’s character. We tried to systematically integrate both of these into SHG programmes because that was the construct, we also passionately believed that savings and credit is something that has the potential to organize women. So, we did not want to leave that out but we also believe that it is possible to integrate a gender perspective. So, we combined both of these from 2011 to 2014; it was four years of a very intensive process supported by the UN fund for gender equality.

How is PRADAN integrating gender concerns in your work on women in agriculture?

We realize that the issue of women’s space in agriculture is a very important issue, but really speaking in women’s lives there are many other issues. When you talk to women, they bring forth a multiplicity of issues, which means that you can’t really compartmentalize their life into issues related to mobility, aspirations, their interactions with public systems, particularly a woman’s experience of violence and such kinds of issues. That’s why I think this work typically tends to move from one issue to another issue, the issues of early marriage, the issues of nutrition, and so on.

Then the emerging question is that she doesn’t have any negotiation potential when she goes to another family because she already goes at a lower status than a man, which makes her position always unequal. So how do you basically equip her with negotiation skills? This doesn’t mean that patriarchy has an impact on women’s lives only. Patriarchy has its own adverse impacts on men also due to their notions of masculinity. So, men also go through their own difficulties, such as being the only one responsible for the household, its well-being and for bringing in the cash.

Another dimension to this is the role of women as care givers. One of the things which I have observed after having interacted with a large number of women across India is that in most cases, they don’t have aspirations for themselves. They generally have aspirations in terms of family, children- “Bacche padhle” (children getting educated), and something along those lines. This is because they have internalized that their existence and role is to nurture everybody around themselves and not really to have any ambition for themselves. However, this is kind of changing in the next generation. I think they have a different kind of a picture of themselves. This tends to also change when you start working with women and collectivizing them. However, their vision/imagination is more of a collective vision rather than probably so much of an individual vision. There’s also a difference in the way a woman would typically articulate a vision. So, when you do visioning, etc., with them you need to be cognizant of these aspects.

What are your core programmes to address the issue of gender in agriculture?

At PRADAN, we have particularly paid a lot of attention to agriculture and allied activities. But, beyond a point, one will have to accept that farm sizes are going down. So, even now we see that households that earn less than INR 40,000 income per annum are the ones where the land parcel size is less than 1 acre. There is a correlation between the resources available and the kind of incomes one can generate, making it all the more incumbent to not only invest in skills, but also into other kinds of enterprises and opportunities. Those are the categories where more efforts are needed.

Nutrition training to Change Vectors

Nutrition training to Change Vectors

Nutrition is also a big focus for us now because we have realized that even though there is more food available nowadays, awareness of what needs to go into a balanced diet needs to be inculcated and internalized within communities and families. For instance, government accrues huge expense on nutrition-specific programmes while the effectiveness of these cannot be really ascertained beyond a point. The message has to be driven in a contextualized scenario rather than just having messages thrown at masses. So, we have tried to integrate nutrition into the crop planning and decision making of rural families. We have also tried to integrate it with the status of a woman’s own health (anemia, etc.) so that she has information about that, and then she knows the reasons behind it. We have seen this type of targeting leading to a change in consumption patterns, changes in diet diversity for the better, even with the same kind of food availability.

Once they internalize it, women tend to gather and consume various kinds of supplementary foods, and also make minor changes such as use of iron vessels, etc. They start to make changes in feeding of young children and infants with the same Take Home Ration (THR) available from the Anganwadi. Earlier, without this kind of consciousness and awareness the entire family was consuming the THR. But now with enhanced consciousness they know the right use of various government supplies (nutrition supplements, etc.), services (immunization, etc.), and so on.

How has this understanding influenced designing and implementation of programmes at PRADAN?

In PRADAN, this kind of nutrition behavioural change communication is now being practiced almost across all the 57 teams. It started as a small pilot. But now there is lot of know-how available within PRADAN, not only on the behavioural change side but also on the agricultural side. We have changed our messaging and communication with communities. So, we are asking them to plan for nutrition security instead of food security now. Earlier, farm families would mostly cultivate cereals and plant pulses and oilseeds on a smaller portion of land but now they give equal importance to all types of foods. So, the area under pulses and oilseeds has seen a marked increase. And also, things like foraging for a lot of greens etc., especially during those times when it is available.

When we look at the context of extension programmes being offered for rural women, more so, the public sector services which are being provided we often see that these consider women only in terms of numbers, that is, the number of women reached, number of women SHGs that are formed, even the number of federations that have been mobilized, etc. The State Rural Livelihood Missions (SRLMs) have done a commendable job in coming up with this huge number federations, etc. However, when this becomes a target approach where you have these many groups, you have these many women, then you link them to banks but then there is an inherent process in bringing them together.

So, within PRADAN, we have a system of doing gender audits – working with our own people in terms of integrating gender perspectives within themselves. One of the biggest impediments in reaching out to communities and specifically to rural women is also peoples’ own perspective. People who are there in the public services domain generally have those kinds of perspectives – “ki isko kuch nahi pata hai” (she doesn’t know anything) and they themselves believe that women have to stay within certain boundaries, this is cultural, etc.

How did PRADAN build an ethos for gender integration not only in its work, but also within the organization?

We had a very strong monitoring component as a part of the programme which helped us observe very significant changes that happened both in terms of changes out there in the community – within collectives and within women’s leadership – a passionate women’s leadership that was triggered during the course of that initiative, but also within PRADAN, within ourselves as professionals. The kind of experiences that all of us went through and shared in our personal lives. Also, many men shared the kind of gender constructs within their own families, how they stood up for their sisters’ share in their households, property distribution, etc. The kind of changes in relationships: within themselves, with their wives, etc. With all these experiences, PRADAN was also mulling over its own development approach and changes in the external environment. And this was one of the strongest inputs. Also, the experiences from the gender equality pilot (Box 1) led to gender becoming the corner stone of the new approach which was articulated by PRADAN in 2014. So, I also feel very fortunate to have been a part of that whole process of influencing the organization to bring about this paradigm shift.

| Box 1: The Fund for Gender Equality The Fund for Gender Equality (FGE) was launched by UN Women in 2009 to support and advance women’s economic and political empowerment at local, national, and regional levels. PRADAN was one of the 13 organisations world-wide that was awarded a grant in July 2010 to implement its programme – ‘Facilitating Women in Endemic Poverty Regions of India to Access, Actualize, and Sustain Provisions on Women Empowerment’. Implemented by a coalition of two national civil society organizations – PRADAN and JAGORI – with extensive experience in mobilizing women around livelihoods and empowerment, this programme sought to work with a large number of poor rural women, including over two-thirds from Scheduled Tribes and Castes, organized into self-help groups (SHGs) and their solidarity associations, in a few states of India beset with endemic poverty. The objective was to enhance and institutionalize their effective economic and political participation impacting their status in family and community, including engagement in local government bodies. This was a pilot project implemented by PRADAN in nine locations with 80,000 women in partnership with UN WOMEN and Jagori. As a result of this project, PRADAN began to engage with livelihood-related issues through a gender lens. Developing women’s identity as farmers has also been the focus of this project.Source: https://www.pradan.net/images/news/mid_term_review_report_revised_17.10.13.pdf |

Did you succeed in providing a conducive space for women within the organization?

Yes, we tried to delve into the issue of whether PRADAN as an organization is providing a conducive space for women to be part of the organization, but somehow it didn’t pick-up the momentum. For six-seven years we went through this whole process where we kept on saying that we are working on intensively advancing gender equality in communities. However, we kept on grappling with how to inculcate it internally within PRADAN. So, the whole discourse picked up in PRADAN in the last five-six years and it started initially with trying to figure out how many women were we able to retain, and then gradually delving deeper into issues of what are the reasons women are not being able to stay back at PRADAN. We also tried to get our head around the kind of gender concerns they had, such as conducive space, and that is a mix of both the policies as well as the day-to-day aspects of behaviour and team functioning, etc., and support systems which are available in times of any conflict. Now we are trying to focus on issues pertaining to how many women are sent to leadership spaces and how many women are actually able to become Team Coordinators, or even Integrators. The discourse is also shifting to not having had a woman as an Executive Director since the inception of PRADAN as an organization.

So, overall, three-four initiatives have been taken up, such as, firstly, to really look at changes in our own recruitment process so basically making shifts in going to places/campuses where there are more likelihood of more women applying, and therefore right from the choice of campuses etc., to the choice of causes, etc. Secondly, looking at it step-by-step, revamping the development of Development Apprenticeship (DAship) curricula to make it more inclusive, and to also have modules around building agenda perspectives for both women as well as men. Thirdly, we established a women’s caucus. Women’s Caucus is basically a support system, an informal mechanism for extending support to women colleagues. Fourthly, we started a system for gender audit of the work spaces. Because the diagnostic exercise showed that there is lot of variation across teams in the kind of culture that is prevalent. So, a gender audit exercise looks at each and every work unit, so as to consider both the infrastructure issues and also the softer issues of team functioning, grooming, nurturing, and mentoring support, etc. So that process is also now institutionalized. I think, two rounds have already been completed in all the work units.

Once the gender audit flags a few concerns, we try to see whether it would need an administrative approach or do we need to bring it to the attention of the various people who are involved. Because the change has to come from within and not really from the top through some kind of administrative order. So, there is a process in which these findings are shared back with the teams and the integrating officers – like the development cluster management committee meetings – then these findings are also shared with the management unit because some actions may require action across the organization. Appropriate actions are required at various levels. Some changes might be needed in organizational policies, but others could be required at multiple levels. I mean there is a three-tier response plan which has now been put in place and it’s now integrated into our reporting cycles, both the plans, as well as the progress narratives that contain what one has done in making the work unit a conducive work space.

One of the main cornerstones of PRADAN’s work has been forging partnerships with government agencies for achieving impact at scale. What has been the main rationale for working with the SRLMs and what are the key takeaways?

What is positive is that all these new institutions which have been built through the SRLMs, etc., are autonomous, and not part of the typical government hierarchy. But they could have been more autonomous than they currently are, and they should try to stay away from acquiring the government character gradually. Another good aspect is that there are people and professionals who are part of these institutions and the fact that they want to do something good. It is challenging because then a person itself becomes the instrument of change and there are no clear answers there. But my own firm belief is that every person wants to do good, and it is this potential for change and that kind of engagement which is required. In comparison to the government probably more autonomy is available which probably is not being exercised. However, the advantage is also the kind of scale that we already have; seven crore women are already mobilized and with some small shifts change can happen at a much larger scale than by simply working individually.

PRADAN CSO partnership

PRADAN CSO partnership

This is not to discount the kind of work we do, I mean there is a lot of importance to that work which serves like a laboratory, like action research, where you can actually try out things, I guess. Eventually, you have to also engage with a larger system which exists and with the initial work that we have done I see a lot of scope for optimism. Moreover, the kind of human resources that are available nowadays, that is, the young professionals who are joining after graduating from institutions like XISS, IRMA, etc., with a different perspective, with a zeal for doing something good in their lives. Of course, there are women whose lives are at stake and they are not passive recipients. So, I think all these together, with some amount of leadership at national and state levels can work wonders. I mean, I am seeing emerging leadership that wants to learn and make changes for the betterment of women and this has been my main reason for optimism.

Beyond SRLM, has PRADAN also been partnering with state governments? How is it going?

We are realizing that forging partnerships with governments is very important, for example, in Odisha, we have this partnership with the Department of Agriculture and Farmer’s Empowerment (DAFE) around promotion of agricultural production clusters. PRADAN is also implementing work in newer areas in the state, apart from its development clusters in Odisha under this project. Along with us, there are 15 other civil society organizations and DAFE and Odisha Livelihood Mission (OLM) are important stakeholders as well. These kinds of partnerships/projects are important for learning by doing at a scale. We believe that training alone doesn’t bring about change. It is actually the training combined with doing an action, taking stock, monitoring, and then improvising which would lead to catalyzing change. So, we have these initiatives now across Chhattisgarh (an initiative around a mega watershed which is basically using the MGNREGA funds for creating livelihood assets), and West Bengal (an initiative called Usharmukti – translated loosely as ‘Freedom from Barrenness’, a land rejuvenation project). These kinds of initiatives which involve both civil society organizations and governments, as well as multiple departments of the government actually create convergence, and learning loops and action.

The core funding for some of these might come from some CSR initiative. For example, Usharmukti is supported by BRLF (Bharat Rural Livelihood Foundation), and similarly Chhattisgarh mega watershed is supported by Axis Bank Foundation, but then core and complementary funding might come from the government (Agriculture Department or MGNREGA) or an amalgamation of donors (Odisha APC is funded by DAFE, BRLF, and now the Gates Foundation too).

Through our work with multiple agencies, we come to know and interact with a lot of pro-active people at all levels (intermediate, middle, etc.) and you can build on the kinds of people who are there until the time that they are there, but then you start off and more people become involved at different levels, and processes get carried out even when that person who might have been the originator of the idea moves on. One can say that scale, and scale alone, is very important. We are realizing that, in these kinds of initiatives because they are at a scale it involves multiple individuals and sometimes these get the attention of political leadership as well. For example, the Odisha APC project was launched by the Chief Minister and the same was the case with the mega watershed project. It is important to have the buy-in of political leadership into these kinds of initiatives because only then can you influence policy, otherwise you might just end up being an NGO which is working in a number of villages and only with a handful communities.

You have these 57 teams, and your work is in very remote and backward regions of the country. How are you organized and how do you contextualize your priorities?

We have around 400 professionals in 57 teams. In 2014, when we did the restructuring which was accompanied by the change in the development approach of PRADAN, it was decided that the teams needed to be closer to communities. Before 2014, we used to have bigger teams based at the district level but in 2014 we reorganized ourselves into block level teams called ‘development clusters’ (DCs). So, these are now smaller teams but based at the block level and each team size is around 5+1 (5 professionals and 1 team coordinator). As to the gender composition of these teams, at the entry level we are now almost fifty-fifty. But, at the team coordinator and integrator level we have approximately 25% women. We have been also experimenting with bringing in lateral hires in some of these positions. So, perhaps not really at the team coordinator level or the integrator level but at least there are some experienced professionals who come with five-six years of experience.

There has been another strategic shift in 2014 where we tried to re-equip and re-tool ourselves for not only building gender perspectives within PRADAN but also in all the new areas of work (PRI functioning, new entitlements, etc.). Therefore, now in every development cluster there are these core groups working on different thematic areas, which are kind of mandated with building new knowledge, and taking this new knowledge to everyone who may be working in that cluster. Every development cluster mostly has these kind of IRGs (internal resource groups). Actually, it started the other way round. Rather than it being an organisational initiative, it started at the bottom. So, the DCs started having these IRGs and looking at that we are now consolidating IRGs at the national, I mean at the organizational level. So, it started as a bottom-up effort, as a response to the new imperatives of knowledge etc., and now at an organizational level also we are forming these groups. For example, now for farm-based livelihoods we have a separate vertical which is actually focused not only on supporting the teams on technical knowledge but also linking them to the various kinds of ecosystem actors (input providers, insurance providers, financial ecosystem actors, etc.) because with agriculture, people now need more working capital, market information, market linkages, FPOs, etc.

PRADAN was not a very prominent name in the FPO space earlier, but we realized that actually farmers need to move. They are not only looking for advice but also for assurance. So, there need to be mechanisms in place by which they feel assured of things like getting inputs on time, being able to sell outputs on time, to name a few. So FPOs can potentially, or agripreneurs can, fill in this kind of a space. So, now the farm-based livelihood vertical is actually focused on creating the required know-how for FPOs and all the various dimensions that have cropped up with it.

67th batch graduation

67th batch graduation

How do you decide on your core priorities?

There was a time after 2014 when there was an abrupt explosion in terms of the kind of things that one was engaging with, for instance, nutrition, domestic violence faced by women, employability, education, etc. Then one found that actually there needs to be some kind of distinction as to what is at the core and what is then leading to spill over effects. Because one can’t really work with equal intensity on everything. So, for us there has to be something which, in our understanding, is at the core, is at the heart of what we do. And that probably in our understanding creates all these spill over benefits etc., say impacts. So, there was a lot of tension I think in that entire process of what is at the heart of doing things and because different people have special efficiencies and distinct values stemming from their own experiences. But I think now what we have that, our canvas is all these – but at the heart of it is Economics, or inclusive economic growth, which leads to empowerment.

So, in some villages we would probably try and work on all the five-six essential dimensions that we are articulating, but in the other areas we would probably focus on the core and hope for these other things. We have tried to distil the indicators for what some of these non-negotiables are in the comprehensive livelihood approach, which is how we are articulating it. So, things like nutrition security that’s one, women’s participation that is women’s say and influence in agriculture, that’s another, then better or improved or carrying capacity of land and water resources, incomes of course are an important indicator at the household level.

How do you measure the impact of your work?

To assess our impact, we have developed indicators for the above mentioned five-six dimensions. Though it doesn’t automatically mean that we are able to measure all, especially the carrying capacity of resources, etc., which is a little difficult to measure at the aggregate level. So, we are still trying to figure out as to how that could be measured. I mean we have been also considering things like men sharing responsibilities of household work, but still there isn’t adequate consensus on some of these because that also requires a much higher level of work and engagement with the men, which currently hasn’t really happened.

Some aspects are easier to measure such as incomes, nutrition security (BMI and diet diversity – these two are very important indicators), etc. However, regenerative agriculture or land and water, better ecological balance, those are slightly tricky which is still not known beyond the area in which work was undertaken, number of water bodies created, and so on, but it needs more rigorous efforts. In some projects (e.g., project with Hindustan Unilever) we are measuring how much additional water has been conserved because of all the work which has been done around bunding, trenching, etc. But it is difficult to really upscale it across other areas.

Some aspects are easier to measure such as incomes, nutrition security (BMI and diet diversity – these two are very important indicators), etc. However, regenerative agriculture or land and water, better ecological balance, those are slightly tricky which is still not known beyond the area in which work was undertaken, number of water bodies created, and so on, but it needs more rigorous efforts. In some projects (e.g., project with Hindustan Unilever) we are measuring how much additional water has been conserved because of all the work which has been done around bunding, trenching, etc. But it is difficult to really upscale it across other areas.

You have a lot of good practices and stories to narrate across different themes. What are the mechanisms in PRADAN to share these within its teams and with the world at large?

We have two-three mechanisms for sharing knowledge. One is an internal mechanism called SAMPARK.NET (https://www.pradan.net/sampark/) – which is a platform on which you can post various kinds of new initiatives that you have undertaken along with photographs and write-ups, videos, etc. So, that platform has been running. Then we have Monday morning motivation stories also. So, every Monday one of the teams shares some things and out of that every once in a week one of those stories is showcased. We have other mechanisms like SAMAGAM (https://www.pradan.net/samagam/) which is a congregation involving other stakeholders in the development space. So, it may be CSOs, it may be CSR organizations, it may be another kind of resource organization at the national level. We just concluded the SAMAGAM in November 2020. This time it was done virtually. We collaborated with PRIA (https://www.pria.org/) and CYSD to organize SAMAGAM 2020 and the event was supported (with logo) by Vani (https://www.vaniindia.org/), FICCI and Niti Aayog. We also undertake research initiatives to actually study various issues with some rigour. So, within PRADAN there is a small research team which is looking at researchable issues, and it takes up at least a handful of research projects every year to study those in more detail and to publish their papers around those learnings.

Where do you think a shift in focus is needed for both PRADAN and other institutions engaging with rural women?

The agenda has to keep evolving, because otherwise there is fatigue and communities’ aspirations also keep growing and one has to be in touch with those aspirations. For example, maybe seven-eight years ago, generating an additional income of INR Rs 10-15,000 was considered enough, but now they are thinking in terms of at least one lakh of income. So, being in touch with people’s ‘aspirations and needs’ is very important. Otherwise, there is a danger of remaining in our own bubble, in our own picture of the level at which we perceive the community’s needs. But people move and have different types of exposure. For example, with the water and sanitation work, now we are talking about piped water supply and drudgery reduction, and one is also getting into all these various dimensions of

PRADAN staff planning with women farmers

PRADAN staff planning with women farmers

quality of life, etc. Also, all these things about next generation and their aspirations are very different and they are probably not looking for the kind of of drudgery being faced in agriculture. They are looking for probably more mechanization, for different kinds of opportunities. The next generation of women also are more literate and ICT savvy, therefore there is potential for them in becoming more mobile. So, now we have women involved in a lot of these, using these mobiles and tablets for various kinds of functions so all that is happening. Yeah, that’s real, an area of change which one has witnessed.

We, as professionals, have kind of neglected engaging with the next generation to some extent. So, that is one area which I think needs more work. And there is this other initiative where we are working with younger women with a much greater focus on younger women. We have seen lots of aspirations in women around various things like picking up their education where because of various reasons they were not able to complete their formal education, especially, class 10 or class 12. So, we are finding that women who are now in their early to mid-20s are coming forward and are very keen to enroll for courses. Through courses affiliated to national institutes of open schooling, with some little bit of handholding and scholastic support, women are now attending classes, coming to the hub and even to the decentralized classes, enrolling themselves and completing it, along with all the other responsibilities they have. Women are also investing in picking up vocational skills.

With the younger generation we need to engage much more than what we have done till now and that is one shift I see in my own work, and it is especially triggered by this work with the younger women. We are working with them around education, around employment, skilling and employment, and around starting some enterprises. It could be farm enterprises, but also off-farm enterprises or allied sectors, etc. So, there is a lot of potential energy that can be unleashed in these areas.

Ms Nimisha Mittal is Lead Researcher, Centre for Research on Innovation and Science Policy (CRISP), Hyderabad, India. You can reach her at nimisha61@gmail.com

Add Comment