In this blog, Aayushi sheds light on the importance and untapped potential of Indian pastoral livelihoods that rely on migratory animal husbandry practices. While outlining the challenges confronting pastoralists, she also identifies crucial areas for targeted interventions that could support these vital yet underappreciated livestock rearing practices.

CONTEXT

When the topic of pastoralism arises in a conversation, it’s not uncommon to be met with blank stares and a general lack of understanding. Despite its historical significance and continued relevance, pastoralism remains an unfamiliar and overlooked occupation. For many, the idea of herding livestock from place to place seems outdated and prompts questions about its practicality in today’s AI and Machine Learning driven world. At the same time, some continue to envision it through a romantic lens, picturing lone shepherds tending to their flocks in remote rural landscapes untouched by the bustling culture of the modern world. However, the reality is far more complex, with nuances and challenges often debated by those unfamiliar with the intricacies of this sustainable way of life.

Pastoralism, as defined by the FAO, is more than just a traditional way of life; it’s a multifaceted production system that contributes to a wide array of products and services made available by rearing livestock in a nomadic manner. From providing essential goods such as milk, meat, fiber, and hides, to offering employment opportunities and serving as a mode of transport, pastoralism plays a vital role in various sectors including agriculture, tourism, and nature conservation. But its significance extends beyond mere economic contributions, as it holds immense cultural value and serves as a crucial mechanism for risk management in diverse ecosystems. Emerging scientific research underscores the environmental benefits of pastoralism, highlighting its critical role in carbon sequestration, water resource protection, and biodiversity enhancement. This ‘time-honoured’ production system utilizes marginal resources and less productive natural landscapes that remain unfit for cultivation. Recent evidence sheds new light on pastoralism’s potential as a nature-based solution to address contemporary challenges in food systems. Simultaneously, the efforts to map the extent of pastoral occupation reveal the vast scope of pastoral livelihoods. Yet it remains surprisingly under-discussed in both food production discourses and policymaking circles.

Changpas of Ladakh

PASTORALISM IN INDIA

Despite the remarkable diversity characterizing India’s pastoral landscape, its significance often goes unrecognized, largely due to its inability to claim central spaces as in the case of industrialized systems of livestock production. Since the colonial period, pastoralism in India has faced neglect, with policies rooted in a colonial past remaining largely unchanged. This way of life is unfairly labeled as archaic and frozen in time, consequently dismissing its relevance and need for consideration.

Although a popular account written in 2003 attempts to capture the diversity of Indian pastoralism, the evolving reality of migratory livestock rearing and its importance to various ethnic and occupational communities across ecological zones remains understudied. Rough estimates suggest that over 13 million people in India practice pastoralism, a figure comparable to the population of a single European country. However, official records of their numbers are non-existent, further complicating efforts to understand and support this vital livelihood.

India holds significant global rankings in livestock production, being the largest producer of milk and buffalo meat, the second-largest producer of goat meat, and the third largest in egg production. Wool exports also contribute substantially to the economy, with an annual valuation of approximately $135 million, showing consistent growth. The livestock sector accounts for almost 4.5 percent of total GDP, with about two-thirds stemming from pastoralist production. However, the lack of disaggregated data that distinguish between extensive and intensive practices makes it challenging to accurately assess pastoral contributions. Additionally, the invaluable contributions of women in pastoral occupations also go unnoticed, despite their significant role in sustaining these livelihoods amidst social, economic, and environmental marginalization.

HERDING IS AN UPHILL TASK, LITERALLY!

The challenges confronting pastoralists in India are as diverse as the diversity they embody. Operationally located at the cusp of various state and central government departments, they have suffered long-standing policy neglect. The forest department, for instance, often labels them as encroachers and a nuisance. With expanding afforestation efforts aimed at carbon offsetting and increasing forest cover, pastoralists are inadvertently displaced from their traditional resource bases. The prevailing fortress model of biodiversity conservation, exemplified by grazing bans and exclusionary park policies, further exacerbates the situation, resulting in loss of pastoral culture, greater economic hardships, and social marginalization.

A Gaddi pastoral herd halting during their summer migration

Indian pastoralists often find themselves obscured by state departments of Animal Husbandry that majorly focus on sedentary livestock rearing. Existing livestock extension services and programs further perpetuate this bias, neglecting the unique needs of diverse migratory systems. Furthermore, there is limited understanding of the extent to which these services reach pastoralists and their efficacy in supporting pastoral endeavors across different states in India. The recent announcement by the Ministry of Fisheries, Animal Husbandry, and Dairying regarding the formation of a ‘pastoral cell’ to address specific policies for pastoralists marks a positive step forward in this direction. However, its effectiveness remains uncertain and has yet to be seen.

Additionally, the rigidity in land classification systems and abrasion of pastoralists’ customary land rights also result in unsupportive land tenure and non-availability of essential resource base that is vital to their livelihoods. Many of the Indian pastoral communities also fall under the purview of the Tribal Ministry, which is responsible for implementation of the Forest Rights Act (FRA). FRA emerged as a hope to formalize pastoral land rights but has miserably failed even after 20 years of its conception, reflecting the inadequacy of state action in supporting pastoral interests.

Moreover, the impacts of climate change pose significant challenges to pastoral communities, particularly those in vulnerable geographical locations. These environmental pressures exacerbate existing tensions, including conflicts with agricultural communities over resources and livestock thefts.

In the face of these multifaceted challenges, the resilience of pastoralists in India is both remarkable and underappreciated. Addressing their issues requires a shift in perspective, recognizing the importance of mobility and adaptive governance frameworks that respect the diverse needs and contributions of pastoral communities. Greater collaboration between government agencies, integration of local knowledge systems into policy-making processes, and empowering pastoralists to participate in decision making are some of the essential steps toward ensuring the sustainability of pastoral livelihoods in India.

NAVIGATING SOLUTIONS FOR PASTORAL CHALLENGES

To support pastoralism in India, a concerted effort is needed to not only recognize its importance but also to integrate it into broader development strategies. Progressing towards the International Year of Rangeland and Pastoralism (IYRP) 2026, a need-based action plan and a holistic strategy that could improve pastoral livelihoods would largely depend on collaborative dialogue among the stakeholders so as to channelize efforts and achieve positive outcomes.

The first step in this direction lies in acknowledging the pastoral existence and accounting for their diversity. By recognising pastoralism as a green economy that does not add to environmental risk, ecological scarcity or social disparity, governments can capitalize on its inherent sustainability to produce for local, national and international markets. Emerging markets for milk and other livestock products could revive the fortunes of herders and provide economic stability in an environmentally responsible manner. However, this can be realised only if pastoralists’ needs – related to their own and livestock’s health – are catered to by ensuring accessible healthcare infrastructure along migration routes.

One innovative approach to support pastoral endeavors involves integrating pastoral livelihoods with eco-tourism initiatives, such as the establishment of resorts managed by pastoral communities in areas like the Banni grasslands of Kutch (Box 1). Additionally, the concept of Eco museums can also be explored to highlight the pastoral bio-cultural heritage, and thus create diversified income opportunities through rural tourism. These initiatives not only help preserve pastoral cultures but also contribute to local livestock economies.

| Box 1: Sustainable Advocacy: Shaam-e-Sarhad Village Resort Located in Hodko village within the Banni region, the Shaam-e-Sarhad (Sunset at the Border) Village Resort is a collaborative effort between the Hunnarshala Foundation, Kutch Mahila Vikas Sangathan, UNDP, and the State Government. This eco-village resort serves as a bridge between traditional pastoralist values and modern society. Shaam-e-Sarhad offers guests a firsthand experience of pastoralist life while promoting the concept of ‘living lightly on the land’. It acts as a platform for advocacy, emphasizing communal ownership and sustainable living practices. By showcasing the economic benefits of common resources and celebrating pastoralist knowledge systems, the resort promotes a harmonious relationship between humans and nature. (Source: http://www.hunnarshala.org/shaam-e-sarhad-village-resort.html) |

With regard to pastoral contexts, governance of tenure also needs immediate attention and steps to strengthen the tenure arrangements by acknowledging the complexity and diversity within pastoral societies. Amidst the labor shortages and youth outmigration, hired herding is also emerging as a promising prospect for continuing mobile pastoral practices and sustaining pastoral livelihoods. Similarly, value addition, product diversification, and management skills training for pastoralists can enhance their economic prospects.

Technological innovations offer another avenue for supporting pastoralism, such as the implementation of smart cards to streamline documentation and permissions for pastoral mobility (Box 2). Advocacy on the global scale is also essential to ensure that efforts to support pastoral communities receive the necessary attention and investments. Lastly, developing extension services tailored to the needs of mobile pastoralists and promoting a participatory approach to capacity building are vital for safeguarding indigenous livelihood practices.

| Box 2: Smart Cards: Tech Solutions for Migrating Pastoralists In response to the challenges faced by tribal pastoral households in Jammu and Kashmir, the Tribal Affairs Department has introduced a technological solution: Smart Cards. These cards, developed in collaboration with the police, Forest, and Census departments, aim to streamline the process of migration and accessing government services for pastoral communities. The smart cards replace the cumbersome multiple permissions regimes with a unified central database, ensuring a hassle-free experience for pastoralists. Embedded with a chip, each card contains vital information such as demographic details, transit routes, and essential statistics. This innovation facilitates efficient movement during migration and provides access to various government services along the way. To further support pastoralists, the department utilizes remote sensing technology and geographic information systems to map pastures and grazing lands across the region so as to understand migration patterns and routes for developing a robust communication network to reach pastoralists in remote areas. (Source: https://centreforpastoralism.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Pastoral-Times-Issue-XIII.pdf) |

In summary, the five priority areas that are to be included in the action plan to support pastoralism in India are:

- Focus on land tenures and recognise dependency on common resources covered under customary laws;

- Streamline mobility facilitation processes through technological interventions such as smart cards, and access to other entitlement services during migration;

- Develop a migration friendly extension system for pastoral populations;

- Offer value addition training and diversification strategies for increased income, alongside fair pricing, and state-supported market linkages for livestock byproducts;

- Develop a clear roadmap for inclusion in the emerging carbon trade market and monetization of ecosystem services provided by pastoral communities.

Gaddi pastoralists tending a sick goat during their way up to the Alpine pastures

ENDNOTE

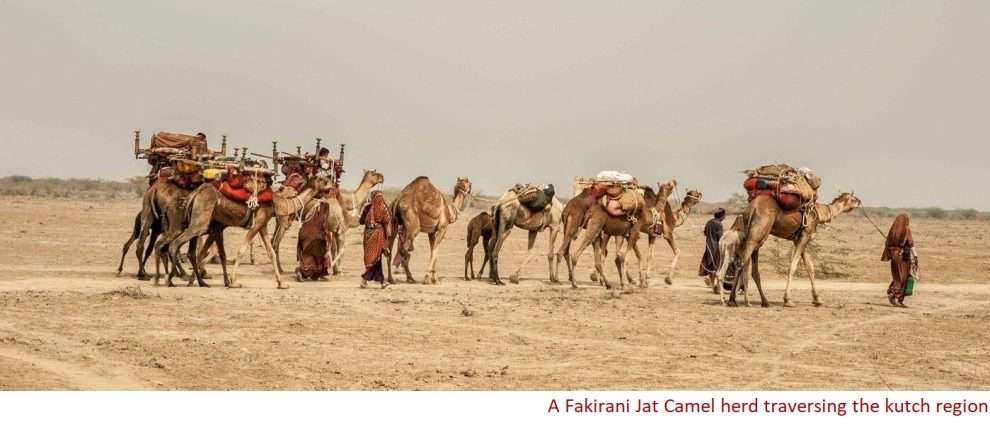

The rich tapestry of Indian pastoralism – ranging from bleating sheep in the north to snorting camels in the west, quacking ducks in the south, and mooing yaks in the east – demands renewed attention. To pause environmental degradation and unsustainable consumption patterns attributed to sedentary, specialized, and feed-intensive cattle farming, pastoralism offers a sustainable alternative. It is by embracing mobility, adaptability, and a deep connection to the land, pastoralists can be supported in the role of climate warriors, leading the charge in agro-ecological transformation. This requires a shift away from the blinkered approaches towards systems thinking. Only by understanding, promoting, and utilizing pastoralism in a holistic manner can we harness its full potential that holds immense promise for a sustainable and resilient future of the food systems.

SUGGESTED READINGS

- Singh R. 2023, February 3. Waves of change: Emerging pastoral advocacy and representation in India. Pastoralism, Uncertainty and Resilience – PASTRES. https://pastres.org/2023/02/03/waves-of-change-emerging-pastoral-advocacy-and-representation-in-india/

- Scoones I. (Ed.). 2023. Pastoralism, uncertainty and development. Rugby, UK: Practical Action Publishing. http://doi.org/10.3362/9781788532457

Aayushi Malhotra is an Assistant Scientist at the CGIAR GENDER Impact Platform, Evidence module and is affiliated to the Gender and Livelihood research team at International Rice Research Institute, New Delhi, India. She is a social anthropologist and holds a PhD in an interdisciplinary field of Environmental Anthropology and Development Studies. Her ethnographic research explores the socio-ecological transitions among one of the Himalayan agro-pastoral communities and sheds light on the intertwined nature of food, gender, labor, and land-use patterns, offering vital insights on the importance of pastoral practices in shaping resilient communities and landscapes. She can be reached at a.malhotra@irri.org.

Aayushi Malhotra is an Assistant Scientist at the CGIAR GENDER Impact Platform, Evidence module and is affiliated to the Gender and Livelihood research team at International Rice Research Institute, New Delhi, India. She is a social anthropologist and holds a PhD in an interdisciplinary field of Environmental Anthropology and Development Studies. Her ethnographic research explores the socio-ecological transitions among one of the Himalayan agro-pastoral communities and sheds light on the intertwined nature of food, gender, labor, and land-use patterns, offering vital insights on the importance of pastoral practices in shaping resilient communities and landscapes. She can be reached at a.malhotra@irri.org.

Refreshing, timely renewed attention to an age-old rural livelihood practice lost in unacceptable negligence to make it highly rewarding to not only to the followers but also rural livestock economy. Very nice depiction of the context, SWOT analysis of the practice/profession, and very professional insights on suggestions/solutions powerfully stated to navigate challenges. The timeliness of the Blog is very befitting to resurrect the rich tapestry and grandeur of the Indian pastoralism in “New Avtar” for contributing to a more promising sustainable and resilient future of the food system. Well written. Congratulations to the author and AESA.