Strengthening the agriculture-nutrition linkage is critical for addressing malnutrition in India. In this blog, Surjit Vikraman illustrates the importance of convergence of agriculture and nutrition-related interventions at the Panchayat level, if we want to be successful in addressing malnutrition at the earliest.

CONTEXT

The nutritional status of a population and the ways and means to improve it has to find a place in the agenda of national governments and various international agencies. Our understanding of the nutritional status of human population, its geographical and socio-economic diversity, and the pathways and determining factors of nutritional outcomes among various communities have improved immensely in the last few decades. The recently launched report of The Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition: Foresight 2.0 presents us with the alarming state of the nutritional status of our population. Now the recent challenges on the public health front with the COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated the associated vulnerabilities and affected the slow progress mankind was making on the nutritional front. It states ‘In 2019, an estimated 26% of the world’s population experienced hunger or did not have regular access to nutrient-rich and sufficient foods. More than 200 million children under five face a life with insufficient food, a situation likely to get worse due to COVID-19’.

INDIA’S NUTRITIONAL CHALLENGES

Agriculture-nutrition linkages as the key strategy

Across the globe, Asia faces the biggest nutritional challenge among all the continents in terms of malnutrition levels among the population, diversity of issues and complexity of the pathways that influence nutritional status. The dominant role played by the agriculture sector in terms of employment generation and livelihood support for its large population makes interventions focusing on agriculture-nutrition linkages very critical for improving nutritional status. In India, nearly 60 per cent of the population is dependent on agriculture for their livelihoods. Hence emphasis on agriculture-nutrition linkages is very important for effective implementation of both supply side and demand side factors that influence nutritional outcomes. There has been several programmes aimed at improving the nutritional status of India’s population of various age groups, with special focus on women and children. The Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) programme, Mid-Day Meal Scheme and the health care programmes of the National Health Mission were designed to address this developmental challenge. Although these programmes focus on supply side factors and is less sensitive to demand side determinants of nutritional outcomes, they have played a major role in the progress the country has achieved on the nutritional front.

Diversity and Complexity of Institutional architecture of nutrition programmes

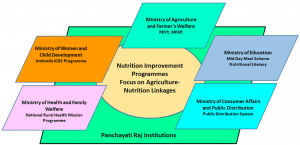

The institutional infrastructure and arrangements made for implementing these flagship programmes to combat malnutrition is very diverse and complex. At the national level four major ministries are engaged in designing, implementing and monitoring the activities of these programmes. There is a great deal of institutional diversity at the sub-national level, particularly at the state level, and it varies to a great extent among the various states in India. In general, the agricultural production and supply management is carried out by the Ministry of Agriculture and Farmers’ Welfare, the ICDS programme is managed by the Ministry of Women and Child Development, the Mid-Day Meal Scheme is implemented by the Ministry of Education, health programmes – including preventive health measures such as vaccination – are implemented by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. In addition to these, the Ministry of Consumer Affairs, Food and Public Distribution, ensures supply of sufficient food materials for the programmes run by all the ministries. All the actions of these ministries have to be coordinated, and handled at various levels (district, block, taluk and village level) for the intervention to reach the target population. This institutional infrastructure is diverse, complex, and of varying strength, especially in the integration among its constituent actors.

NEED FOR ENHANCED CONVERGENCE

There needs to be a great deal of convergence among these institutions in order to effectively implement nutrition improvement programmes for better results. It is also critical for facilitating demand side interventions, which is currently absent in many of these programmes. Hence convergence between theses ministries, which are public institutions, can enhance the impact of the ongoing programmes and is effective in improving the efficiency of actions along various pathways for better nutritional outcomes. A representative convergence strategy for better nutritional outcomes is given in Figure 1. In addition to convergence among various arms of public institutions, there should be effective convergence with various institutions in the private sphere as well as civil society. Such a convergence will have a multiplier effect on ongoing programmes and activities and contribute significantly to improvement in the nutritional status of the population.

| Box 1: Diverse Challenges on the Nutritional Landscape Globally 88 per cent of countries face a serious burden of either two or three forms of malnutrition. The Global Nutrition Report 2020 estimates that ‘1 in 9 people – 820 million worldwide – are hungry or undernourished and raises concerns about global nutrition equity.’ We also have become concerned about the growing levels and nature of various forms of inequalities, socio-economic discriminations, and have realised the fallacy of associating economic growth with better nutritional status. Over the last two decades, fighting malnutrition has been at the centre stage and in the forefront of the developmental agenda laid out by MDGs during the 2000s to be achieved by 2015, carried forward by international agencies such as WHO Commitments on malnutrition to be achieved by 2025, leading up to the Sustainable Development Goal target of Zero Hunger by 2030. Countries across the globe have taken steps to develop policies, strategies and programmes to achieve the targets laid out by international alliances to fight malnutrition. However, despite the best of efforts by nations, malnutrition continues to be a critical challenge that defines our development outcomes. Assessments and experiences shows that there is huge diversity in the levels, patterns, determinants of various indicators of nutritional status of population across the world and therefore the policies, strategies and interventions should be specific and sensitive to the socio-economic specificities that define the diversity of nutritional landscape. In addition to these diversities, there are two major concerns that transgress the landscape that defines nutritional outcomes across nations in the world. The first one is the realisation and the concern about levels, nature and characteristics of growing inequality and its ‘invisible’ effects on nutritional outcomes, and the second one is the challenge of public health vulnerabilities to the incidence of pandemics, such as COVID-19 and the consequent impact on nutritional levels of population. These concerns make the pathways that affect nutritional outcomes complex, diverse, demanding sustained efforts to make some progress. |

Panchayati Raj Institutions as platform for convergence

Panchayati Raj Institutions as platform for convergence

1.The Global Nutrition Report 2020 analysing the trend in progress of the WHO 2025 target states that ‘The trend is clear: progress is too slow to meet the global targets. Not one country is on course to meet all ten of the 2025 global nutrition targets and just 8 of 194 countries are on track to meet four targets’.

2. For example, malnutrition and dietary risks are the two most important risk factors that drive death and disability in India. Malnutrition was the predominant risk factor for death in children younger than five years of age in every state of India in 2017, accounting for 68•2 per cent of the total under-5 deaths, and the leading risk factor for health loss for all ages, responsible for 17•3 per cent of the total disability-adjusted life years (DALYs).

STRATEGIES FOR BETTER CONVERGENCE: STATES SHOW THE WAY

In a country like India with wide-ranging geographies, varied agro-ecologies and diverse cultures, achieving convergence is a mammoth task. However, certain initiatives are happening in this direction in different states. To cite a few of them, there are initiatives in the states of Chhattisgarh, Telangana, Odisha and Kerala, that has made some progress in bringing convergence among various institutions and actors engaged in addressing the nutritional challenges of the country.

Chhattisgarh State presents an interesting case where convergence between the MGNREGA, Department of Horticulture, and Department of Women and Child Development has created a model which supplies nutritious food to members of the ICDS programme in Dhamtari district. The Agriculture Department has organised vegetable cultivation in its farm – engaging MGNREGA workers – and supplying the production to ICDS centres in the block. This has ensured a diversified and balanced diet to the children and pregnant women in the block. The engagement of MGNREGA workers have ensured the creation of purchasing power among the vulnerable population in the area. Similarly, in Sukma district under the initiative of the district functionaries of the Women and Child Development Department, select anganwadi centres have set up small vegetable gardens which grow locally available vegetable seedlings, and its yield is included in the food served to women and children. This is a commendable example of convergence among public institutions that has worked well towards creating better nutritional outcomes.

ICDS Centre at Dhamtari District,Chhattisgarh

ICDS Centre at Dhamtari District,Chhattisgarh

In the state of Odisha, women SHGs were mobilised under the umbrella of Odisha Livelihood Mission activities to set up entrepreneurial ventures that produce food for supplementary nutrition initiatives. These SHGs were given training under the banner of Mission Shakti programme to produce the Take Home Ration supplied through ICDS centres to pregnant women and children. Women empowerment through various ways is embedded as an integral component at different levels of the implementation mechanism in the nutrition programmes of Odisha. This is an example of convergence between ongoing nutritional improvement programmes and institutions formed to improve livelihoods and empowerment of rural women. It also ensures facilitation of demand side interventions by providing entrepreneurial opportunities which also complement the interventions under nutritional improvement programmes.

ICDS Centre at Koraput District, Odisha.

ICDS Centre at Koraput District, Odisha.

In Telangana State, in addition to the standard ongoing programmes for nutritional improvement, the government has roped in private sector players to complement these efforts. The resources from private firms have been mobilised by voluntary agencies to provide support to the Mid-Day Meal Schemes in different schools in selected locations. An interesting feature of this initiative is the way in which individual and organisational philanthropy efforts has been streamlined to support nutrition improvement programmes, and contribute to their implementation through proper monitoring mechanisms. This programme also plans to engage with the agricultural production system to meet the demands for vegetables and other food materials for the programme. Once established this will facilitate promotion of effective agriculture-nutrition linkages for better nutritional outcomes.

Kerala State presents a unique case with promising and emerging institutional convergence where Panchayati Raj Institutions (PRIs) are trying to create a platform for integration and collective action of various departments together with people’s action for creating sustainable livelihoods. Here PRIs, which are the grassroot level institutions, coordinate the functions and activities of the four major departments responsible for programmes aimed at improving nutritional status of the population. This ensures that PRI functionaries who represent people’s collective efforts and voices play a major role in implementing the programmes. It also promotes integration and convergence between actions of the key departments contributing to efficiency in implementation and better impact. In addition to that, a comprehensive oversight of the programmes by people’s representatives ensures transparency, better monitoring, and creates ownership among the beneficiaries. The most notable feature is that apart from functioning as a social audit mechanism, people’s voices at the grassroot level get heard, and play a major role in defining the nature and pace of interventions.

The four cases mentioned above – the cases of Chhattisgarh, Odisha, Telangana and Kerala states – present distinct examples of promising initiatives of convergence among institutions of various forms and nature engaged in improving nutritional outcomes. These initiatives demonstrate the potential of convergences among various arms of public institutions, between public and private institutions, among public, private and institutions of decentralised governance leveraging the strength of people’s action in implementing, monitoring, and improving the effectiveness of programmes that focus on rallying nutritional status of the population.

Furthermore, there is a greater realisation of malnutrition as a major developmental challenge, but the pathways that define nutritional outcomes are complex and involve multiple sectors and stakeholders that call for convergence and sustained long term efforts. Historically interventions have largely focused on supply side issues, but demand side interventions need to be given more attention. In a country like India with diversity and complexity in all aspects, specific interventions are required for impact that is sustainable and inclusive.

ICDS Centre at Garo Hills, Meghalaya

ICDS Centre at Garo Hills, Meghalaya

CONCLUSION

There are three critical components that need urgent attention and intervention. They are given below.

- There is an urgent need for convergence across policies, programmes, activities and institutions at all levels among the various stakeholders and this is critical for improving nutritional outcomes.

- Women empowerment and leadership for women in all spheres of intervention, particularly in creating sustainable livelihoods, promoting entrepreneurship, decision making and monitoring of nutrition programmes is critical.

- Creation of convergence platforms at the grass root level through decentralisation of governance mechanisms – by strengthening of PRIs and empowering them to design, implement and monitor interventions – is essential for improving nutritional status of the population.

References

- Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition. 2020. Future food systems: For people, our planet, and prosperity. London, UK. Available at https://www.glopan.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Foresight-2.0_Future-Food-Systems_For-people-our-planet-and-prosperity.pdf accessed on 02-10-2020

- Global Nutrition Report 2020: Action on equity to end malnutrition. UK: Development Initiatives Poverty Research Ltd.

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. 2020. Country profile for India. Available at http://www.healthdata.org/india accessed on 03-10-2020

- Swaminathan S et al. 2019. The burden of child and maternal malnutrition and trends in its indicators in the states of India: The global burden of disease study 1990–2017. LANCET Child and Adolescent Health 3(12):855-870. Available at https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanchi/article/PIIS2352-4642(19)30273-1/ fulltext accessed on 03-10-2020

“The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the organisation”.

Dr Surjit Vikraman is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Agrarian Studies, School of Development Studies and Social Justice, National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (NIRDPR), Hyderabad. He has a PhD in Economics and his areas of work include: Agrarian relations in India, Value chain analysis and development, Agriculture – Nutrition linkages, and Agricultural policy and impact assessment. He has 15 years of experience in working on agrarian issues and has previously worked at the International Potato Research Institute (CIP) and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). He can be contacted at surjitvikraman.nird@gov.in

Dr Surjit Vikraman is an Associate Professor at the Centre for Agrarian Studies, School of Development Studies and Social Justice, National Institute of Rural Development and Panchayati Raj (NIRDPR), Hyderabad. He has a PhD in Economics and his areas of work include: Agrarian relations in India, Value chain analysis and development, Agriculture – Nutrition linkages, and Agricultural policy and impact assessment. He has 15 years of experience in working on agrarian issues and has previously worked at the International Potato Research Institute (CIP) and the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT). He can be contacted at surjitvikraman.nird@gov.in

“Congratulations to Dr Surjit Vikraman on presenting successful initiatives taken in effectively implementing the ICDS in four states and the necessity for convergence to achieve the desired results especially when different ministries are involved in implementation of ICDS. I think it is better to study the way the Akshaya Patra Foundation, an NGO based in Bengaluru is successfully implementing mid day meal scheme and serving about 1.8 million children spread in more than 12 states”.