Using the case study findings from a concurrent monitoring technique called process monitoring conducted as a part of a large-scale government project called JOHAR being implemented in the Indian state of Jharkhand, Vinod Hariharan, Phalasha Nagpal and Gurpreet Singh highlight the role of agricultural extension services (e.g. awareness creation, market support etc.) in agriculture and allied activities in rural India. This note provides evidence of the potential of these services in nudging behavioural change and in turn positively influencing sales revenue and further in turn household incomes of the socio-economically vulnerable households, particularly of women, as a social group.

CONTEXT

Agricultural extension is critical to the transfer of technological information and know-how to the people engaged in farming and allied activities. Despite being a state subject, agriculture extension activities are implemented by both state and central agencies such as the Department of Agriculture and Krishi Vigyan Kendras, as well as Producer Groups (PGs) and Non-Government Organisations (NGOs). Traditionally, extension approaches in India followed a top-down approach (Singh et al. 2013). However, the implementation of projects such as Diversified Agricultural Support Project (DASP) from 1998-2004 and National Agricultural Technology Project (NATP) from 1999-2005 funded by the World Bank have effectively incorporated demand and supply side dimensions to extension approaches (Raabe 2008). The Jharkhand Opportunities for Harnessing Rural Growth (JOHAR) project, initiated in 2017, co-funded by the state government and the World Bank and implemented by the Jharkhand State Livelihood Promotion Society (JSLPS), also follows both supply and demand driven extension approach.

ABOUT JOHAR PROJECT

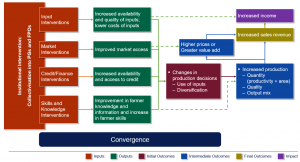

The project is being implemented across 68 blocks from 17 districts in rural Jharkhand with an aim to enhance household incomes of the beneficiaries. This is designed to be achieved by enhancing livelihood sources such as High-Value Agriculture (HVA), livestock, fisheries and Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFP). The project targets about 200,000 beneficiaries who are women from the rural households, also members of the Self-Help Groups (SHG) formed under the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) with the potential to generate marketable surplus from their livelihood sources. The theory of change for JOHAR (JSLPS, 2020) illustrated in Figure 1 shows that beneficiaries are collectivised to form PGs and Farmer Producer Companies (FPCs).

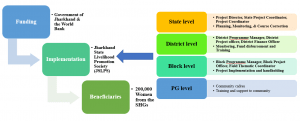

PGs are formed after a five-day PG formation drive in the villages based on its potential in the livelihood activity promoted by the project. Interested beneficiaries join the PG for the livelihood activity promoted in JOHAR after contributing membership fee of INR 100 and share capital of INR 1000 for FPC. A total of 3,923 PGs have been formed till date with membership ranging from 25 to 125. The beneficiaries in the collectives are provided with interventions across key dimensions- input, market, credit, skills and knowledge. These are designed with the aim to nudge a behavioural change among the beneficiaries with the longer-term objective of enhanced sales revenue and in turn, household incomes. The stakeholders of the project and their role is mentioned in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Theory of change of JOHAR project

Figure 1. Theory of change of JOHAR project

The JOHAR project has included the cascading model of training of trainer approach. This involves dissemination of knowledge about new and improved practices and technology, provision of support to PGs in input procurement and marketing of the produce, and communication of beneficiaries’ demands and grievances to the project staff. The trainers are a pool of cadres identified and selected by the PG members from amongst themselves based on the candidates’ previous experience in the livelihoods promoted in JOHAR project and in community institution building under National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM). The pool of cadres are selected during the PG formation drive and their roles at PG level in JOHAR project are given in Table 1[1].

Figure 2. Stakeholders of the JOHAR project

Figure 2. Stakeholders of the JOHAR project

Table 1 List of cadres at PG level and their roles in JOHAR project

|

# |

Name of the cadre | Cadre description | Role in PG |

| 1 | Active Women (AW) | Nurturing of PGs on management and governance aspects |

|

| 2 | Bookkeeper (BK) | Maintenance of books of records in PG |

|

| 3 | Ajeevika Krishi Mitra (AKM) | Assist PGs in enhancement of area and production under HVA activity |

|

| 4 | Ajeevika Pasu Sakhi (APS) | Assist PGs in enhancement of livestock activity |

|

| 5 | Ajeevika Matsya Mitra (AMM) | Assist PGs in enhancement of fishery activity |

|

| 6 | Ajeevika Vanopaj Mitra (AVM) | Assist PGs in enhancement of NTFP activity |

|

| 7 | Technical Service Provider (TSP) |

Assist water user groups formed in PG and maintenance of irrigation schemes installed in PG under JOHAR |

|

All the project cadres are trained by block and district level project staff and provided with Information, Education and Communication (IEC) materials for training the PGs, by the respective project implementation teams at state level for training the project beneficiaries. AW and BK are trained during the PG formation drive. Technical cadres like AKM, APS, AMM, and AVM are trained in scientific production of the select activity engaged by the PG before the start of activity. The refresher trainings are also provided to the cadres by the project as per project requirement. The AW in turn trains the PG members on PG management and governance within 45 days after PG formation. The trainings in selected livelihood activities by technical cadres are conducted after successful completion of trainings by the AW. All the trainings to the cadres are free. The project has provision for skilling the cadres with support from Agricultural Skill Council of India (ASCI). The PG members are supported by all the cadres after they take up a livelihood activity through crop monitoring, disease and pest management services.

Disease management by APS

Disease management by APS

These cadres submit their monthly work report to the PG. The monthly payment to the cadres is provided by the PG after the review of the work done report by PG office bearers. The PGs receive funds for payment of cadres from project after submission of the work done report by the cadres at the Block Mission Management Unit (BMMU).

This extension approach plays an important role as the community members are being trained by members selected by them and can potentially increase the uptake of new and improved technologies at the community level. We provide case studies based on our learnings from the concurrent monitoring technique called process monitoring conducted at the PG level under the JOHAR project. These case studies highlight the importance of extension services in bringing about behavioural change among the beneficiaries in large scale projects.

CASES OF INTEREST

A comparative study of two PGs in the same revenue village

The contrasting cases of two PGs in the Burakadhi village of the East Singhbhum district presented an interesting case study during the JOHAR process monitoring.

Since the time of its formation in 2018, the first PG had been undertaking collective farming with its 28 members engaging in crop planning for High Value Agricultural (HVA) crops. Input loans provided within the project through the PG and were repaid in time along with a 2 per cent interest payment. The premise of collecting interest from the members was aimed at meeting the recurring costs of the PG. Thereafter, it was noted that with time, given the potential of gains from PG membership and collectivisation, the number of PG members increased to 62.

In 2019, all the members of the first PG undertook crop planning during the winter season while availing loans from the PG for productive inputs like seeds/seedlings, pesticides and fertilisers. Thereafter, the PG members collectively started engaging in a more active role in tapping markets (such as the farmer producer companies) where they would command a better price for their produce. We found that the key drivers of the PG activities were the strength and timeliness of extension services. The AW trained the PG members effectively and thereby encouraged a higher uptake of PG activities.

Despite its proximity, the second PG did not compare well to the former. To begin with, both the PGs undertook first crop planning for HVA during the same period. However, this PG did not receive any input loans at all, barring ten members that received lemongrass input loan. However, due to the poor timing of input support, the lemongrass cultivation became unviable.

The key contrasting factors between the two PGs were highlighted by the Field Thematic Coordinator (FTC) of JOHAR project shown in Table 2.

| Particular | PG 1 | PG 2 |

| Cadre retention rate | high | high |

| Participation in training by the cadres | Most cadres had attended the meeting and had effectively trained and supported PG members | Cadres not undertaken the requisite training |

| Hand holding support to PG members by the cadres | Strong hand-holding support to PG members by the cadres as a result of which the PG was more active | Due to low cadre retention rate and low training levels among them, PG was inactive |

| Internal PG meetings | Meetings were conducted periodically | Meetings were not conducted periodically contravening project guidelines and theory of change |

| Leadership support to the PGs | PG leadership was active due as a result of trainings during PG formation by ICRP cadres and AW. For instance, it was found that the AW of the PG was a Bank Sakhi and all the members worked coherently under her leadership | The PG had poor quality of leadership as AW of the PG did not perform their duties and were diverted away from PG activities and leadership as had assumed other roles |

PG member setting insect traps

PG member setting insect traps

Success of Lemongrass cultivation after incurring losses in fish production

Another story of interest is that of a PG in the Bero block of Ranchi district. What is both interesting and vexing is how extension services provided by the JOHAR project played a critical role in enhancing rural livelihoods. Despite facing substantial losses owing to fish cultivation, the PG members of Bero Block have been able to gradually enhance their incomes through lemongrass cultivation.

To provide some context, during the 2018 round of process monitoring it was learnt that the members of this particular PG had been incurring substantial losses through fish cultivation. Generally speaking, Jharkhand faces a paucity of perennial water bodies which thereby affect the sustainability and profitability of fish cultivation. In this case, it was noted that the households had incurred a significant loss due to their failure to undertake pre-stocking and post-stocking activities. This included cleaning the water body and assessing the water quality for fish health- key prerequisites for fish cultivation. Resultantly, the quantum of production was low, and economies of scale could not be leveraged leading to losses. To hedge the losses from fisheries development, it was learnt that the ten PG members decided to take up a more profitable livelihood activity-lemongrass cultivation. They undertook this activity through active consultation with the PG cadre who supported and guided them in their initiative. To this end, they were supported by the JOHAR project with funds equivalent to INR 52,250. Following this, the sale of lemongrass slips (stems) to the other PGs yielded them a total earning of INR 2.88 lakh. They went a step further and utilised the lemongrass leaves to process them and make lemongrass oil. It was noted that the members had stocked 7.5 litres of oil (market value=INR 2,500/1,000 millilitres). Furthermore, it was noted that to begin with, they had collectively cultivated lemongrass over one-acre of land. Learnings about the profitability prospects of lemongrass cultivation coupled with the support of the extension services in training, sourcing quality lemon grass slips and crop management, their risk appetite increased. Consequently, in the following year, they expanded the land under cultivation to over 2.5-acres.

Community cadres of JOHAR who received ASCI certification

Community cadres of JOHAR who received ASCI certification

It was learnt that the success of lemongrass cultivation by this PG encouraged the other villagers to join the PG. It presented them with evidence of opportunities to leverage the project’s support and extension services in the form of training and crop monitoring, for moving towards more sustainable and profitable livelihood activities.

CONCLUSION

The case studies shed light on factors that contribute to the strengthening extension services that can be pivotal to the successful implementation of large-scale projects like JOHAR at the micro and macro-levels. Firstly, the providers of extension services such as cadre members played a supportive role in ensuring adherence to processes and collectivisation under the project. It was found that an active, well-trained and incentivised cadre can be critical in nudging a higher uptake of PG activities by its members. Such a cadre is well-positioned to provide continued support and guidance to the PG members as well. Secondly, the extension services such as training were provided to the PG members in time and empowered them to take up livelihood enhancing activities. Thirdly, and critically, there was willingness from the PG members to leverage the extension services like training, crop, disease, pest and market advisory services, for their benefit and initiative as well as a commitment at their end. Such a combination of supply and demand-side support to extension services has the potential to make a PG to become self-sustainable and enhance rural livelihoods.

REFERENCES

Jharkhand State Livelihood Promotion Society. 2020. Jharkhand Opportunities for Harnessing Rural Growth Project- Impact Evaluation Baseline Report. Rural Development Department. Government of Jharkhand. Retrieved from: http://jslps.org/wp-content/uploads/JOHAR-IE-Baseline-Report.pdf

Katharina R. 2008. Reforming the agricultural extension system in India. What do we know about what works where and why. Development Strategy and Governance Division, International Food Policy Research Institute Discussion Paper, 775.

Singh KM, Meena MS and Swanson BE. 2013. Extension in India by Public Sector Institutions: An Overview. MPRA Paper 49107, University Library of Munich, Germany, revised 16 Aug 2013.

FOOTNOTE

[1] JSLPS (2020) Community Operational Manual for JOHAR, Version-4

Vinod K. Hariharan is an Assistant Consultant in Oxford Policy Management India Private Limited (OPMIPL), New Delhi, India

Phalasha Nagpal is an Assistant Consultant in Oxford Policy Management India Private Limited (OPMIPL), New Delhi, India

Gurpreet Singh is the Project Co-ordinator, JOHAR project, Jharkhand State Livelihood Promotion Society (JSLPS), Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

Gurpreet Singh is the Project Co-ordinator, JOHAR project, Jharkhand State Livelihood Promotion Society (JSLPS), Ranchi, Jharkhand, India

“I appreciate the JOHAR project management in improving the skills of the local leaders to help the farmers in enhancing income through agriculture and allied activities. As indicated by the authors through contrasting case studies of Producer Groups, selection of the local leaders play a very important role in the success of the project. Clarity may be given on the following aspects in the project. 1. Why the project management did not consider the option of taking up good fish rearing practices? 2. What made them to think of lemon grass cultivation instead of promoting fish production? 3. The project is providing loans to the members for input purchases @ 2 %. Is it 2 % per annum or 24 % per annum? 4. It appears that the expenditure on cadres and other persons is being met from the project funds. It may be worthwhile to indicate the amounts paid to these cadres. How the project management is aiming at sustainability of the project after the financial support from the project is withdrawn? 5. If this project is to be replicated elsewhere in a cluster of villages what would be the likely expenditure? Thanks to Vinod Hariharan, Phalasha Nagpla and Gurpreet Singh for sharing their experience of working with women to enhance their livelihoods and to AESA for making it available to us”