In acknowledgement of International Day of Forests (March 21), Aditya Mandloi and Alark Saxena from Development Innovation Foundation (DIF) share their findings on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on forest and forest-dependent communities. This blog highlights their observations from the villages in the Ratapani Wildlife Sanctuary (RWS) in Madhya Pradesh, India.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, the COVID-19 pandemic has challenged food security, public health, working structures and supply chains. There has been a huge disruption in the economic, social and environmental patterns of India. While journalists, scholars and development practitioners have discussed the impact of COVID-19 among urban and rural communities, forest dwellers have generally gone unrecognised. In forest villages – where general accessibility is also low –communities remained unsure of what the pandemic demands. They speculated about the whole situation from what they saw on television, social media, and first-hand narrations from migrants who came back to their respective villages. In this blog, we focus on the findings of the research work done by Development Innovation Foundation (Box 1) in the villages in the Ratapani Wildlife Sanctuary (Box 2) in Madhya Pradesh.

| Box 1: About DIF and our ongoing research Development Innovation Foundation aims to innovate, implement and promote initiatives towards the sustainability of people and the planet. DIF is invested in finding solutions for effective natural resource management, biodiversity conservation, decentralising renewable energy, and building sustainable cities and communities. It is currently involved in understanding the challenges of the pandemic on forest and forest-dependent communities during COVID through a research project titled ‘Creating evidence for forest based resilience’ conducted in Madhya Pradesh, Himachal Pradesh and Assam, funded by the Swedish Research Council. Through a mix of qualitative enquiry, household surveys, and remote sensing analysis, we are assessing the role of forests in household coping strategies during the pandemic, the impacts of changing forest use on forest structure, and identifying policies associated with greater socio-ecological resilience. This research will directly contribute to establishing evidence in terms of the role of forests as a safety net during times of crises, and this blog is based on the findings from this research |

The villages in the RWS have a mix of various kinds of livelihoods that sustain them through the year. These are: agriculture; wage labour (farm and non-farm); migration for wage labour (short term and long term); livestock rearing; collection and sale of Non-Timber Forest Produce (NTFP); shops and services, and pension funds.

|

Box 2: Forest and Wildlife in Ratapani Wildlife Sancturary (RWS) |

Forest Patches near Lulka Village, Raisen

Forest Patches near Lulka Village, Raisen

The people around RWS practice agriculture as their primary livelihood option. The land holdings are relatively small, and on average, a household holds 1-2 acres of land. Due to the rocky structure of land and soil, that permeates the Vindhya Ranges, the productivity of the land is also low (Soils of Raisen District, ICAR). Most of the households practice subsistence farming only. Agriculture is mostly rainfed here as there is no irrigation facility, so people go for work outside the village as daily wage labourers in the off-season. Landless people are involved in farm and non-farm wage labour.

The livestock in around 50% of households are used for household consumption. Only the Gurjar community in a few villages are involved in the commercial selling of milk and other dairy products. Almost all households use forests for collecting fuelwood, NTFPs, grazing of livestock and leisure purposes. The NTFPs include Mahua, Tendu, Achar, and the occasional extraction of medicinal plants by a few elderly women in the village.

Livestock grazing in the patches of Community Forest near RWS

Livestock grazing in the patches of Community Forest near RWS

IMPACT OF COVID-19 LOCKDOWN

Forest dwelling communities strongly depend on forests for their livelihoods. In an attempt to prevent the spread of coronavirus, the government put restrictions on the movement through forests. This affected the supply of essential commodities and stopped the collection of minor forest produce, such as gum, honey, bamboo, beedi leaves, tamarind and broomstick grass. Moreover, the items they make, like siali leaf plates, rope from siali bark, and an alcoholic juice – salap, harvested from salap trees, are highly perishable (Mohanty and Choubey 2020). These items need a proper weekly market to add value to forest dwellers’ lives. The National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) banned all human movement inside all the 50 tiger reserves throughout the country following the news that tigers could be infected by the novel coronavirus (Aditya and Ravikanth 2020). However, there were varying levels of enforcement in terms of forest access in different parts of the country. For instance, some forest areas of Upper Assam were relatively lenient with their restrictions. The forest-dependent communities were collecting what is available in the forest for their subsistence (Aditya and Ravikanth 2020). The weekly local markets (Haats) of rural and forest villages came to a halt during the lockdown (Mohanty and Choubey 2020).

The impacts were as follows:

Agriculture

In the first lockdown, they faced a lot of difficulties as the markets were closed and they were unable to procure the basic input materials for their farms, such as seeds for sowing, manure, insecticides, and pesticides. All the nearby markets were closed so people started growing vegetables in their homes for consumption. People who sold their produce in Mandis (society), received standard payment while the ones who sold their produce in the open market, suffered some losses.

Livestock

With regard to the Gujjar community, their main profession is rearing cattle for milk. Gujjars on an average have 5-10 cows per house. Their sales reduced drastically, so they mostly consumed the extra litres of milk. They also converted it into other dairy by-products like ghee to increase the life and price of the commodity.

Labour

As the market for wage labour in the vicinity of the village went down to zero, households faced difficulty in earning and procuring grains for consumption. This was especially true for landless households that were solely dependent on wage labour. However, the family networks within villages supported each other for the most part. Due to the lockdown, the people were unable to get out of the villages. Gradually, rich and capable farmers bought machines which further reduced requirement of labour. Youth of the village, who were just graduating from 12th class or diploma, also stayed back till the lockdown and other restrictions eased so that they could go to nearby cities such as Obedullaganj, Mandideep, or Bhopal in search of jobs.

NTFPs

The flowering of Mahua is dependent on weather conditions. However, the price for Mahua decreased during the lockdown. In the normal scenario, Mahua would go for around INR 100/kg, while in the lockdown, it went down to about INR 40-50/kg. This really decreased the income that forest dwellers usually generate in the April season.

Inflation

The labour wage remains the same but the prices of commodities such as petrol, cooking oil, and spices (mainly salt and chilli powder) has been on the rise. The prices almost doubled in a period of six months. For instance, cooking oil increased to INR 170/litre which was INR 70/litre before the lockdown. Even now the price remains unchanged.

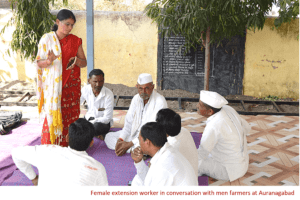

Interaction with Women on health, livelihoods and drudgery

Interaction with Women on health, livelihoods and drudgery

Food security

Some households received extra grains that the government promised under the COVID Relief Package (INR 20.9 trillion), announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi on 12 May 2020 (Dev 2020). INR 100,000 million was transferred to 200 million women in India holding special Jan Dhan accounts (INR 500/female/month for three months) (Sengupta and Jha 2020). However, the ration was only provided to households with ration cards. A vast majority of households that didn’t have ration cards didn’t receive any extra ration or cooking fuel.

Entitlements under Government Schemes

A very few households received the promised INR 1500 in their account. The money was transferred to women Jan Dhan Accounts.[1] The money was transferred in three months – of INR 500 each – during April to June 2020. The same scheme by the government also promised front-load of INR 2,000 paid to farmers in the first week of April 2020 under the Pradhan Mantri Kisan Yojana. This effort was also only half met on the ground, and just a few people got the money in their accounts.

STRENGTHENING LIVELIHOODS: WHAT COMMUNITIES LOOK FOR

Integrating MNREGA with NRM

Approximately 90% of the people didn’t have job cards in MGNREGA. In some cases, the attendance of the people working under MNREGA wasn’t properly marked, and thus they were not paid. Moreover, the communities face grave problems of water for domestic as well as agriculture purposes.

Assessing the condition of water bodies of the villages with community members

Assessing the condition of water bodies of the villages with community members

This situation offers potential for two things:

- The integration of MNREGA with NRM-based works, such as deepening of ponds, digging and rejuvenation of wells based on resource mapping, better watershed management and installation of public tube wells. Such an intervention will help in generating employment and creating assets that will be beneficial to these communities in the long run.

- Strengthening of MNREGA as an institution. In such remote parts of the country, the MNREGA scheme is still to penetrate to its full potential. If the National Rural Livelihood Mission (NRLM) departments can team up with local NGOs or community members, they can accelerate the creation of job cards, thus registering more people for MNREGA work. Further on, regular monitoring will also help in checking any malpractices within the system.

Better healthcare facilities

It was observed that whenever a person, especially the earning member of a family, faces a major medical issue, the financial situation of the family worsens. It requires only one such incident for a family to fall back into the poverty trap.

There is a need to fortify such safety nets in the form of government schemes and better health care facilities, and then work on the extension services. These services would include the means to reach and use services, confidence to communicate with healthcare workers, awareness about the existing healthcare benefits and means to avail them, etc. Enhancing the availability and accessibility of basic healthcare facilities can help in improving livelihoods, and thus, income.

Strengthening of Village Level Samitis (Committees)

There are various committees in villages such as the Van Samiti (Forest Committee) and Talaab Samiti (Pond Committee) which help in the governance of the commons – community forests, ponds and grasslands. Proper training of these committees will result in better governing of the commons while developing social capital. A community with elevated social capital is bound to take better unanimous decisions and hold the system accountable.

Food security through self-reliance

Approximately half of the households did not have any livestock or poultry of their own. With the land available for grazing, the community members should at least be able to rear livestock for their subsistence. This will also help in improving the nutrition levels of families, and further help the community achieve food security. There is potential to form Self Help Groups (SHGs) of women, make them creditworthy and provide them loans for a goat shed or chickens in their homes. These activities will help them lead a better life.

Better market linkages

There is a need for better backward, forward and financial linkages. With financial linkages, such as opening of bank accounts, the community members will be able to access the benefits provided by the government, for example, depositing of INR 2000 during the lockdown. Moreover, it will also help in getting better credit services to farmers for their agricultural and allied needs. There is potential to grow vegetables and fruits in their backyard for their own consumption as well as for sale. This will happen with both backward and forward linkages. Building the capacity of forest dwellers to grow vegetables and a network of vendors that can purchase the produce from the village can add another source of income for them.

MOVING FORWARD: ROLE OF EXTENSION AND ADVISORY SERVICES (EAS)

Though life is slowly going back to normal, COVID-19 and lockdowns have had an impact on forest-dependent communities, which can have far reaching consequences in the long run. While a few development actors are supporting farmers with extension and advisory services, more needs to be done to strengthen the livelihoods of these forest-dependent communities in the area of vegetable production, vocational training, and sustainable extraction of wood.

Vegetable Production

Community members who have started growing vegetables are continuing the practice. This way they are not only more self-sufficient but are also providing better nutrition to their family. This trend is expected to go on as they have already been immersed in these practices. More members will join in for the commercial production of vegetables given that there are sufficient market linkages and better supply of water.

| Actors supporting vegetable production | Current responsibilities | Recommendations for strengthening service provision |

| Department of Horticulture and Food Processing,

Food Processing Industries

Local Mandi Contractors |

|

|

Villagers growing vegetables in their backyard

Villagers growing vegetables in their backyard

Vocational Training

In a few villages, people have set up small general shops upon seeing the opportunity in COVID times. These shops were opened by the entrepreneurial people who saw the gaps in the supply and demand for basic commodities in the village. At present there is an overload of shops, but since factories have reopened, the people from the villages will again be fleeing to towns in search of better pay and better lives. More and more youth from the villages are turning to cities for livelihoods and are getting basic jobs in the nearby factories. Some factories are even providing pick up and drop facilities for women workers. With the increasing population of youth in the villages, this pattern is sure to exist for a long time.

| Actors involved in vocational training | Current Responsibilities | Recommendations for strengthening service provision |

| Department of Technical Education, Skill Development and Employment,

Rural Youth,

Corporates

|

Vocational training and placement

Courses in digital format for Distance Education; Strengthening linkages of technical education institutions with industries for mutual benefits.

|

Promotion of RNF (Rural Non-Farm) sector which has shown promising growth in the last five years;

Strengthening financial education and financial counselling of small shop and business owners; Provision of micro-credit at lower interest rates; Organising gender inclusive vocational training for women workers; Conducting need assessment of skills for industries and prioritizing the related learning outcomes. |

Sustainable Extraction of Wood

Extracting fuelwood by forest-dependent communities for cooking, heating, etc., is a necessity. A few households have started to use LPG for making tea and curries. However, after the first free LPG cylinder empties, people don’t buy a new one when they can extract fuelwood for free. There is a need for innovative and better designed chulhas that consume less fuelwood and produce less smoke inside houses.

| Actors Involved | Current Responsibilities | Recommendations for strengthening service provision |

| Forest Department, Government of Madhya Pradesh,

Local NGOs,

Local Politicians,

Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas (PM Ujjwala Yojna),

Public Health and Family Welfare Department |

Protection and conservation of forests while maintaining the integrity of the existing ecosystems;

Ensuring better livelihoods for forest-dependent communities;

Ensuring sustainable extraction of forest produce;

Providing LPG connections to women from Below Poverty Line (BPL) households. |

Bettering accessibility to LPG cylinders;

Better awareness and communication to use smokeless chulhas;

Designing and providing efficient smokeless chulhas to resonate with the current system;

Generating awareness, especially among women, on respiratory health. |

CONCLUSION

With ongoing research, we are aiming to find concrete evidence for forest cover change, forest use and forest dependence of communities for affirmative action. At DIF, we are striving to find gaps and opportunities for fortifying such communities with sustainable and scalable solutions.

As we see different livelihood trends coming in for forest-dependent communities, they will have to face more such shocks in the future. It is only the communities that are resilient to the shocks, such as climate change, global warming, SARS like diseases, nationwide lockdowns, etc., that will have better chances of surviving and not falling back into the poverty trap. EAS has a critical role to play in supporting these forest dwelling communities.

References

Aditya V and Ravikanth G. 2020. How the pandemic has affected India’s forest-dwelling communities. https://coronapolicyimpact.org/2020/05/06/how-the-pandemic-has-affected-indias-forest-dwelling-communities/

Dev SM. 2020. Addressing COVID-19 impacts on agriculture, food security, and livelihoods in India. https://ebrary.ifpri.org/utils/getfile/collection/p15738coll2/id/133824/filename/134027.pdf

Mohanty A and Chiubey AG. 2020. The lockdown has worsened the plight of Odisha’s indigenous Bonda community. https://coronapolicyimpact.org/2020/06/01/the-lockdown-has-worsened-the-plight-of-odishas-indigenous-bonda-community/

Sengupta S and Jha MK. 2020. Social policy, COVID-19 and impoverished migrants: Challenges and prospects in locked down India. The International Journal of Community and Social Development 2(2):152-172.

ICAR; SOILS OF RAISEN DISTRICT. National Bureau of Soil Survey & Land Use Planning (ICAR). http://14.139.123.73/bhoomigeoportal/publication_pdf/district_publication/Raisen.pdf

Tomar S. 2019, July 22. Madhya Pradesh government to declare Ratapani sanctuary a tiger reserve. https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/ratapani-to-be-made-a-tiger-reserve-soon/story-7QloUEIkXbuFnCJkMHnhMP.html

Foot Note

[1]Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Package (PMGKP)

Aditya Mandloi is a Program Associate at DIF, Bhopal, and a graduate from Indian Institute of Forest Management. With regard to his research work, he is carrying out an exhaustive analysis of forest dwellers’ life, their livelihood trajectories, forest resources quantification, patterns in the flowering of Non-timber Forest Produce (NTFPs), market linkages and migration routines. Aditya adopts an interdisciplinary approach to find holistic solutions for effective natural resource management. (Email ID – aditya.mandloi@dif.dev ).

Aditya Mandloi is a Program Associate at DIF, Bhopal, and a graduate from Indian Institute of Forest Management. With regard to his research work, he is carrying out an exhaustive analysis of forest dwellers’ life, their livelihood trajectories, forest resources quantification, patterns in the flowering of Non-timber Forest Produce (NTFPs), market linkages and migration routines. Aditya adopts an interdisciplinary approach to find holistic solutions for effective natural resource management. (Email ID – aditya.mandloi@dif.dev ).

Alark Saxena is an Assistant Professor of Human Dimensions of Forestry at the School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University. He is a forester turned social ecologist, a complex system scientist, and a systems modeler. He is interested in mainstreaming climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction in the development processes of marginal communities across the world. Currently, he is focusing on developing techniques for evaluating resilience to shocks and stressors, particularly in developing countries. (Email ID – Alark.Saxena@nau.edu )

Alark Saxena is an Assistant Professor of Human Dimensions of Forestry at the School of Forestry, Northern Arizona University. He is a forester turned social ecologist, a complex system scientist, and a systems modeler. He is interested in mainstreaming climate change adaptation and disaster risk reduction in the development processes of marginal communities across the world. Currently, he is focusing on developing techniques for evaluating resilience to shocks and stressors, particularly in developing countries. (Email ID – Alark.Saxena@nau.edu )

Happy to see being inclusive writing so well on forest dependent people! Way back in 1999 I supervised a Master’s thesis on Forest dwelling livestock keeping community-Van Gujjars of Uttarakhand, published a few papers and blogs.

http://wca2014.org/milking-the-forests/#.YjKikRhX40M