In this blog, Arpita Sharma and Anaisha Sharma reflect on how gender is socially constructed and how we can tweak these through dialogues within and outside the family.

CONTEXT

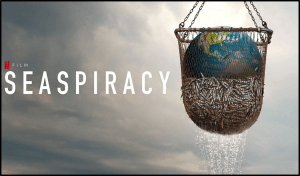

The theme of this year’s United Nations World Oceans Day is ‘Life and Livelihoods’. In this context, the importance of oceans for every species is very well known, so I will skip that discussion and jump to an interesting documentary film named Seaspiracy which many of us have seen. All who have watched this documentary film must be wondering what the social accountability of this sector is, and if the journey of food produced from different water bodies has been responsible enough.

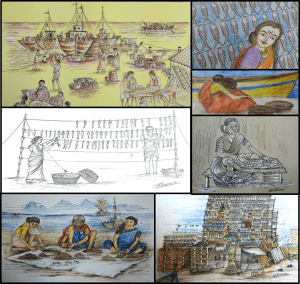

Well, personally speaking, I saw this documentary with my teenaged daughter and son. We appreciated the way it was made. But my daughter commented, “Where are the women in this sector, why are they not shown and why is that so?” I tried to explain that women are present everywhere – pre-harvest, harvest and post-harvest.

Based on her understanding, she gave her review about this documentary and said, “I am going to raise this topic for a moderated caucus in my next Model United Nations conference”. There she wanted to have a dialogue with the delegates from various countries and hoped to create a draft resolution and get it approved and passed by the committee. She began to gather her thoughts so as to have a discussion with her friends.

My son had his share of advice for both of us and said no one should be prisoners of their own biology. He further stated a pertinent point that there are more differences within a gender than between the genders.

To this I agreed – the truth about gender is that there are more differences within gender than between gender! Men and women are more similar than different, but we are trained to focus on and develop the differences. So gender is not binary but a continuous category. A person can be more or less feminine or masculine.

Well, based on the mother-daughter-son reflective discussions, I thought of penning this down. It was a coincidence or should I say icing on the cake, that I received an email from Dr Rasheed Sulaiman where he appreciated one of my webinar talks on social construction of gender and asked me to write a blog on it. So this is the background to the writing of this blog, but I would like to first start with some clarity of terms such as ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ first.

Based on my theoretical and practical understanding, I realise that ‘gender’ is socially constructed and ‘sex’ is a biological construct (Box 1).

|

Box 1: Sex and Gender |

During my conversations, I have realised that explaining biological construct is always relatively easier by simply mentioning that as soon as a child is born it is granted a physical sex label, i.e., female or male.

The difficult part to be understood is when it is said that the newborn is immediately and forever ‘gendered’ through social interactions. This includes norms, behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man, girl or boy, as well as relationships with each other.

The difficult part to be understood is when it is said that the newborn is immediately and forever ‘gendered’ through social interactions. This includes norms, behaviours and roles associated with being a woman, man, girl or boy, as well as relationships with each other.

But during talks, I usually get a reaction that this social construct can differ from country, state and even from family to family. Yes, this is right as this social construct may vary from society to society and can change over time.

Coming back to the discussions with my daughter, I thought of bringing up the topic again during lunch time. So while drinking water, I turned the discussion towards ownership of open water bodies, especially the discussion that water is for everyone.

As expected I got a reaction about why I am making it look as if water itself is discriminatory. Water does not discriminate between anyone, so in that sense water has always been gender neutral. So then why do we need a discussion on this?

Well, I tended to disagree to this and placed a counter question – if this is so then why is the relationship of people and water not gender-neutral?

Even though I had said it, I felt this was not easy to explain. All the same I took this opportunity to address this question by moving the discussion onto the social construction of gender. So I took the role of a teacher which I usually do when I teach the course on ‘Gender, Livelihood and Development’ for Master’s students of Fisheries Science at ICAR-CIFE, Mumbai.

So here in this blog, I want to explain how the social construction of gender happens.

SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF GENDER

When I say social construction of gender what I mean in short is that ‘social beliefs’ create ‘norms’ which lead to ‘gender roles’ and ‘sexual division of labour’ with productive jobs for men and reproductive jobs for women leading to ‘different activities and tasks’ for men and women. This creates ‘differential access to and control’ over resources and ‘differential decision making and power’. However, an understanding of the social construction of gender – in detail – is necessary for the readers of this blog.

So let us start with social belief. Social beliefs are the beliefs by which groups in a community identify themselves.

These social beliefs create norms. Norms are accepted standards, or a way of behaving or doing things that most people agree with. Different gender norms are defined which govern the behaviour of men and women in society (e.g., men can express themselves, men can be articulate, women must not express themselves or be articulate).

Different gender norms define different gender roles for men and women (for example, men must be breadwinners; women must be carers/nurturers).

This leads to sexual division of labour with productive jobs for men (jobs which earn incomes/wages) and reproductive jobs for women (caring, nurturing, social reproduction) and community/formal leadership for men (e.g., Sarpanch) and informal leadership without public or formal recognition for women (e.g., dai, wise woman).

Sexual division of labour leads to different activities and tasks for men and women (women’s tasks are undervalued and invisible, e.g., cooking, cleaning, women’s work is fragmented; so public domain for men, private for women).

This leads to the ‘differential access to and control over’ resources (resources such as money, land, technology, knowledge, self-esteem, time, space).

This further leads to differential decision making and power.

SO WHAT IS THE PROBLEM?

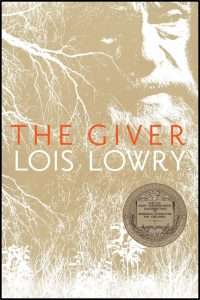

One may tend to ask what the problem in social construction of gender is. Every society will have some sort of construction and we cannot have a completely utopian or a dystopian fictional community or society, can we?

One may tend to ask what the problem in social construction of gender is. Every society will have some sort of construction and we cannot have a completely utopian or a dystopian fictional community or society, can we?

Talking about fictional community or society, I remember a novel which was there in my daughter’s school curriculum in Grade 7. She recommended that I read the novel and what a great novel it was! The novel called The Giver is written by Lois Lowry. I found it paradoxical in that it has won critical acclaim on one hand but has also been banned in certain countries. The book starts with a society which appears to be utopian through sameness – with the community lacking colour, memory, climate, etc., in an effort to acquire a sense of equality. But as the novel progresses it reveals how this society is constructed to be dystopian by its very sameness. The book set me thinking about who makes these decisions.

The real problem in social construction of gender is that those who make decisions and have power are the ones who influence social beliefs and gender norms on behaviour, sexual division of labour, and access to and control over resources. (I also need to say here that if done with fairness this same problem can be a strength too.) Thus, this is a system which feeds on its subsystems and perpetuates itself.

The beauty of the system is that it can be broken anywhere, either by changing social beliefs, or by changing norms for behaviour of men and women, or by changing the work that men and women are supposed to do, or in the allocation of resources. Thus, the gender constructs can be changed over time, over space, and over contexts.

It is necessary to understand that social construction of gender does not happen in one day. It is a continuous process in which both individual and wider society plays a part and goes on from one generation to another. This construction is not something that we do not know of, and this is not fiction. It is what each one of us sees and lives on a daily basis.

It is necessary to understand that social construction of gender does not happen in one day. It is a continuous process in which both individual and wider society plays a part and goes on from one generation to another. This construction is not something that we do not know of, and this is not fiction. It is what each one of us sees and lives on a daily basis.

Now the question is: If this social construction of gender has not been beneficial for one gender how has it survived for so long? Isn’t it intriguing, therefore, that this social construction of gender has survived from one generation to the next!

In this context, I would say that it has amazing survivability behaviour. Despite there having been many men and women who have tried to break this social construction of gender, it has survived. This has survived so long due to the fact that it keeps updating, adapting, reinventing and even modernising from time to time, generation to generation. There are many examples when this construction has been challenged and gains have been made and will continue to be made. However, these changes are small and yet to become revolutionary and transformative in nature.

WHAT SHOULD WE DO?

Now, the important point to note and accept is that social construction of gender has the ability to update, adapt, reinvent, and modernise. So what should be done? It is necessary for us to update, adapt, reinvent, modernise and keep challenging the traditional social construction of gender and play a major role in stopping its perpetuation.

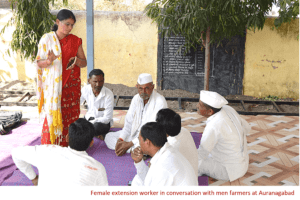

One way is to have these discussions and debates with family, friends, students, and colleagues even when our beliefs are conflicting, because it is only through conversations that we can ignite minds. As social scientists we go to places, we travel all over the world, we talk to people, we read and we write but are we witnessing any radical changes. Not really.

One way is to have these discussions and debates with family, friends, students, and colleagues even when our beliefs are conflicting, because it is only through conversations that we can ignite minds. As social scientists we go to places, we travel all over the world, we talk to people, we read and we write but are we witnessing any radical changes. Not really.

This is because social construction is shaped by the interests of certain groups. If a voice is raised some change will be done whether in ‘social beliefs’ or ‘norms’ or ‘gender roles’ or ‘sexual division of labour’ or ‘differential access to and control’ or ‘differential decision making and power’. In every generation this construction will be tweaked a certain bit and it will appear as flexible. But in the guise of some misinterpreted value system the social construction of gender will be shown as rational and legitimate. That is the reason change within our current gender system is difficult and slow, but not impossible.

After a discussion with my daughter, son, and many young students, I am cautiously optimistic and I believe that society can, and will, change. So continuous engagements are critically needed.

Dr Arpita Sharma is Principal Scientist, Social Sciences Division of ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education (ICAR-CIFE), Mumbai, India. (email: arpitasharma@cife.edu.in and arpita_sharma@yahoo.com.

Dr Arpita Sharma is Principal Scientist, Social Sciences Division of ICAR-Central Institute of Fisheries Education (ICAR-CIFE), Mumbai, India. (email: arpitasharma@cife.edu.in and arpita_sharma@yahoo.com.

Anaisha Sharma is a Grade 10 student at Jamnabai Narsee School, Juhu, Mumbai. (email: anaisha.sharma5@gmail.com)

Anaisha Sharma is a Grade 10 student at Jamnabai Narsee School, Juhu, Mumbai. (email: anaisha.sharma5@gmail.com)

Illustrations by SK Sharma (email: sksharma.icar@gmail.com) and Jaya Pant (email: jayarpant@yahoo.com)

A must read excellent blog for today’ s stereotypic society??

Very informative blog.

Very nyc mam, this article is really impressive!!!

Very informative write up,thanks

Arpee let me congratulate you and your daughter for the brilliant article on social construction of gender and dialogue with youth..really an eye opener, fud for thought as we take it upon ourselves to don the gender garb as things of propriety without even probing a yard further, as to why and how these cannit be thought of from a different perspective…loved ur excerpts from the documentary film seaspire..

??????????

Thank you Naila, Ifrah, Suchismita and Dr. Jayanta for such encouraging and kind words. Thanks a lot Dr. Swathilekshmi from whom I have learned so much.