As humanity prepares to celebrate the Ocean during the World Ocean Day on 8 June, Dr C Ramachandran reminds us of the need to protect the human rights of sea-going fisherfolk through adequate legal instruments.

CONTEXT

“Acting responsibly is not a matter of strengthening our reason, but of deepening our feelings for the welfare of others”- Jostein Gaarder in Sophie’s World[1]

The most striking outcome of the recent verdict[2] by the International Tribunal on Law of the Seas (ITLOS) on what is generally known as the ‘Enrica Lexie incident’, which India wanted to be known as the ‘St: Antony incident’, is that nobody vouches for protecting the right to life, the most fundamental of all human rights, of those who do fishing for a livelihood in our Exclusive Economic Zone. Everyone waxes eloquently on the way these instruments as well as the rhetoric (peer reviewed and avant garde) are going to play a radical role in making a better, safer and more sustainable world for the fisherfolk of the world (Box 1).

|

Box 1: No dearth of rhetoric |

But I find that none of this academic effervescence on human rights have apparently come to the court rooms[8] that tried to resolve a case where two Indian fishermen who, while engaged in legitimate fishing activity in the Indian EEZ, were killed by two Italian military officers who were on private security duty on board an Italian oil tanker.[9] I should add a small correction here. It is not correct to say that no reference at all was made on human rights in this case. It appears that the Italians were the first to take the human rights route, probably due to the presence of a human rights legal expert in their team. They argued that the human rights of these two accused Italian citizens were violated by the Indian government by not giving a charge sheet to the accused even after two years of litigation, and by denying their humanitarian requests for medical treatment and spending Christmas days with their dear ones!

It seems that the human rights argument came to the Indian team as an after-thought, but thus fortuitously making the issue an unprecedented two-way affair, throwing legal luminaries into a tizzy of legal debates and discourses around human rights in the context of the Law of the Seas.[10] But the most important point is that neither party raised any specific human right in this case (Papanicolopulu 2015).[11] Why did the issue of Human Rights not get the attention it ought to have received[12] while the case remained so explosive? What can be done now?

HUMAN RIGHTS OF FISHERFOLK

Answers to these questions cannot be sought in a neutral space, for human life is not an academic abstraction. It is a lived reality written in blood, bones and tears. (Box 2). To paraphrase Taleb,[13] a fisherman does not need to win arguments, just fish. But when it comes to the question of his or her life as a question of law, we have to see that he wins in arguments too. It is here, I argue, that we lost a crucial opportunity in ensuring the human rights of fishers, not only Indian but from anywhere in the world, who are fishing in their respective EEZs. I would like to avoid the small scale fisheries label here, for the simple reason that human rights cannot be relegated to such undefinable[14] polarities of big and small.

|

Box 2: Do we really care about the human rights of fishermen? |

Whether big or small, black or white, the right to life is a fundamental human right for all homo sapiens. So the rights of even those who use the sea space of this planet for livelihood – whether legal or illegal until proven by due course of law – needs to be defended, protected and sustained.

MY TAKE ON POSSIBLE REMEDIES

- UN should urgently bring reforms in the UNCLOS.[17] A clarification regarding the rights and authority of a coastal state in taking criminal procedures against anyone who takes the life of their fishermen who are normally pursuing a livelihood in the EEZ is immensely important in preventing our fishing grounds from turning into killing grounds.[18]

- We must be less enthusiastic in trying to implement international guidelines which are touted as voluntary. While honouring the normative intent and importance of such instruments [19] with sincere respect, I dare to say that it is a waste of precious resources if no attempt is made to draw up binding rules from these guidelines before implementing them in signatory countries. I think assessing ‘implementability’ must be a prerequisite before pushing it as international agreements so that member nations have a clear idea about its policy/legislative instrumentality. And also to see whether it is in sync with the socio-economic and ecological nuances existing in the respective fishery contexts. The real litmus test here, is to answer the question “who owns it”?[20] Reification may engender a false answer.

- National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) should come out with a legal instrument for protecting the rights of fishers in India.[21]

- The Committee on Fisheries (COFI) of FAO should moot a similar international instrument and make it binding.

- All merchant vessels should be equipped with an SOP, including state-of-the-art devices such as high quality telescope, warning mechanisms which are functional during day and night (all weather conditions), and there should be a mechanism to ensure that they are in constant communication with the Coast Guards of the respective coastal states.

- Any fisher stakeholder who is given a licence or registration should sign a mandatory declaration on human rights under a modified Marine Fishing Regulation Act or other policy instruments.

- Indian fishers should be made aware of the inevitability of multiple and transnational uses of the sea space and the crucial need for following sea security protocols stringently.[23]

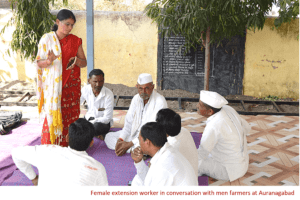

- Building up a global community of all those who have a concern towards, as well as are willing to voice the human rights issues faced by all those who ‘journey the last frontier’ is the need of the hour.[23] Fisheries Extension professionals may play a role in synergising the translation[24] among legal experts, fisheries scholars, fishers and others. Experts-mediated transparency as a way to ensure right to information is essential, given the legal complexities involved in HR issues.

- An honest judiciary as well as executive introspection on the case will be of much value to all human rights crusaders.[25]

- Declare 15 February as International Day for Human Rights at Sea.

Concluding this personal reflection, I fervently hope that a well-reformed UNCLOS and new international instruments geared towards human rights at sea will provide the necessary arbitrational armour and moral strength for all those who wish to fight for justice for seagoing fishers anywhere in the world.

Let me urge each one of you who honour the call by UN in dedicating this year’s World Oceans Day for Human Rights at Sea to remember two names in the silence of your heart: Jelastine and Pink.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Dr Rasheed Sulaiman V, for inviting me to write this blog. I have avoided the conventional style and instead chosen the ‘footnote framework’. I think this style enables quicker understanding especially when we have the benefit of living in a Google world. I have omitted many important references, which I have benefited immensely from, for the simple reason that they are paywall-protected. And it is not a secret the way I got access to them!

I am sure that this blog may not jell with the political correctness of many who happen to go through this. I take the sole responsibility for all the personal opinions expressed here and I don’t intend any malice towards anyone. Nor are the views expressed here not subject to correction. I would be extremely happy to receive comments and criticism. But my only request to you is if you are not lucky enough so far to have ever gone on a sea-fishing trip, kindly do so at the next best opportunity you get. And read this blog again ….. And anyone who enjoys the unique status of simultaneously being blessed with any knowledge from any branch of fisheries science and fish as well, at least occasionally, I request them to be kind enough to have a conversation with me. The future belongs to them.

I am sure that this blog may not jell with the political correctness of many who happen to go through this. I take the sole responsibility for all the personal opinions expressed here and I don’t intend any malice towards anyone. Nor are the views expressed here not subject to correction. I would be extremely happy to receive comments and criticism. But my only request to you is if you are not lucky enough so far to have ever gone on a sea-fishing trip, kindly do so at the next best opportunity you get. And read this blog again ….. And anyone who enjoys the unique status of simultaneously being blessed with any knowledge from any branch of fisheries science and fish as well, at least occasionally, I request them to be kind enough to have a conversation with me. The future belongs to them.

My special regards are always with Ms Meryl Williams (eminent Australian agricultural research leader and former Director-General of the World Fish Centre from 1994-2004). I dedicate this blog to the painful memory of Valentine Jelastine and Ajeesh Pink.

Footnotes:

- Sophie’s World (Norwegian: Sofies verden) is a 1991 novel by Norwegian writer Jostein Gaarder.

- Permanent Court of Arbitration award on case No. 2015-28 dated 21 May 2020, could thankfully settle an eight-year long dispute that badly affected diplomatic relations between India and Italy.

- UDHR of 10 December 1948 is the most famous international legal instrument, though not binding, on human rights. Human rights are a legally protected interest inherent to man and intended to ensure his or her dignity as a human being from the State and from other human beings (Ndiaye TM. 2019. Human Rights at Sea and the Law of the Sea. Beijing Law Review 10:261-277). India imbued the spirit of the UDHR while framing the Constitution of India. Articles 14–30, 32, 226 of the Constitution of India (1950) ensures human rights under the fundamental rights. Articles 5-11, 325-26 also reflect UDHR aspirations.

- The architecture is well known and not dealt with here. RP Remanan (2014), Mehtha and Verma (1999) could be handy references.

- FAO Voluntary Guidelines for Securing Sustainable Small-scale Fisheries in the context of Food security and Poverty Eradication (2015 first edition and 2018 second edition, often referred to as FAO SSF Guidelines) is a landmark publication. Though the FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF 1995), which is considered as the bed rock of global fisheries management, is conspicuous by the absence of any reference to ‘human rights’. FAO’s (2009) ‘CCRF and indigenous peoples – An operational guide’ tries to address this lacuna.

- Google search yielded 131,00,000 results for two key words (Human rights, fisheries governance), and together with the third word (+India) threw up 734,00,000 results.

- The Pulitzer-prize winning book by Ian Urbina, The Outlaw Ocean (2019), tops the bestseller chart in this genre.

- I don’t have access to the court documents and I have resorted to indirect measures. For instance, the Google search with four key words (Human rights violation, Enrica Lexie case, UNCLOS, FAO SSF ) yielded just 29 results, out of which only one publication honoured all the key words. It is titled ‘The future of ocean governance and capacity development: Essays in honor of Elisabeth Mann Borgese (1918–2002)’ / edited by the International Ocean Institute-Canada, Dirk Werle, Paul R Boudreau, Mary R Brooks, Michael JA Butler, Anthony Charles, Scott Coffen-Smout, David Griffiths, Ian McAllister, Moira L McConnell, Ian Porter, Susan J Rolston and Peter G Wells (2018).

- This incident happened on 15 February 2012. The mechanised trawl boat (St Antony), registered under the Tamil Nadu Marine Fisheries Regulation Act (1983) and Marine Product Export Development Authority (MPEDA) Act, had 11 fishermen on board and was fishing 20.5 nautical miles off Kerala coast in what is known as Contiguous Zone, but outside Territorial Waters which is reserved for non-mechanised fishing vessels. Whether Indian government, being the coastal state has the power to charge criminal procedures under the Indian Penal Code (IPC) on the Oil tanker whose flag state was Italy, was a crucial point in the legal tussle. The argument that Italians could avail the benefit of immunity under United Nations Convention for the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was upheld by ITOLS raising many legal brows.

- Notable and freely accessible ones are: Irini Papanicolopulu. (2015.) Considerations of humanity in the Enrica Lexie case QIL – Zoomin 22:25-37. Grover & Gupta. (2021.). Violations of human rights under the semblance of sovereign immunity. The Daily Guardian. Honnibal. (2020.) CIL, Singapore. Atul Alexander. 2020. opiniojuris.org, etc.

- I would like to consider this as the most abominable lapse because the winning argument of immunity, which Italy has been consistently arguing, could have been counterweighted by the Human rights argument.

- There were attempts to attribute terrorism (Gardiner Harris 2014, The New York Times), but not human rights.

- Taleb NN. (2018). ‘Skin in the game – hidden asymmetries in daily life’, like many of his other books, is a hilarious read. Thank you Taleb.

- The current thinking is short of a universally acceptable definition, let each nation bring its own definition. No wonder there is a ‘not small enough cry’ in the air, similar to the reservation clamour we are familiar with. One is reminded of Sainath’s Everybody loves a good drought.

- Phronesis is a Greek term which means ‘practical wisdom’ that has been derived from learning and evidence of practical things. Phronesis leads to breakthrough thinking and creativity, and enables the individual to discern and make good judgements about what is the right thing to do in a situation.

- An art, skill, or craft; a technique, principle, or method by which something is achieved or created.

- United Nations Law of the Seas convention (10 December 1982) is considered as the constitution of the sea. This is not a human rights instrument per se. As Papanicolopulu, a well-known scholar on human rights and law of the seas, observes in her book, ‘The problem with UNCLOS and other laws of the sea instruments is that they are designed for States and not for individuals. The law of the sea is a State-centred regime, in which States have the rights (and obligations) while people may at most be considered as beneficiaries.’ Human rights as per UNCLOS is an incidental issue. Being the dominant legal instrument applicable to the seascape it is essential to remedy the grey areas as revealed in the context of the Enrica Lexie case. It seems to me that the PAC circumvented a reformist nudge by endorsing the immunity argument instead of addressing the Indian question on the authority of a coastal state to exercise its domestic legal instruments in its EEZ in cases where human rights of its citizens are violated. The international legal community has to allay the concerns of a fisher when he asks “What is the guarantee that I will not be shot dead while I do legitimate fishing in our own waters?”.

- This is all the more important given the fact that instances of our fishermen interfacing with merchant ships, often leading to casualties, are on the rise these days. As inshore waters are becoming less productive, and given the technological advances changing class and labour-relations (demanding new interpretations in coastal/shorelines-conflict) our fishers are at risk in such encounters. Another reason is the proximity of their fishing grounds to international shipping channels as in the case of Kerala coast. The question of piracy needs to be addressed as a multi-factor (tax havens, bunkering facilities, poverty & inequity, structural adjustment, etc.) developmental issue.

- Both the FAO voluntary instruments (CCRF as well as SSF guidelines) were translated by me into Malayalam and I have developed various extension tools for the promotion of these concepts among the fisherfolk stakeholders in India. I must also mention that I got a very rare opportunity to be part of an international expert group that conducted a multi-country ‘Evaluation of FAO’s support to the implementation of the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries’ under Dr Meryl Williams. I also invite your kind attention to my book titled Teaching not to Fi(ni)sh – A constructivist perspective on reinventing a responsible fisheries extension system. It is also worth mentioning here that the FAO SSF guidelines are dedicated to the memory of Chandrika Sharma, of the International Collective in Support of Fish workers (ICSF) which is the main driving force (formulation and advocacy) behind the instrument.

- I remember Simon Funge-Smith, who pointed out the irony in probing the implementation of a voluntary instrument.

- The NHRC plays a crucial role in addressing the human rights issues faced by those fishermen getting jailed in Pakistan and Sri Lanka. It is strange that despite the availability of various IT-based forewarning alert devices our fishers still trespass into the international maritime border inviting jail terms in foreign countries.

- It is pertinent to note that Italian security officers, in their plea, alleged that the absence of an Indian flag on St Antony was a factor in deeming the unidentified boat as a pirate boat. They also questioned the validity of the licence issued by the Tamil Nadu government, which has jurisdiction only in Territorial waters, for fishing in the Contiguous Zone. India argued that the vessel had MPEDA certificate of registration, but not under Merchant Shipping Act. Though the tribunal dismissed Italy’s allegations in this regard, there seems to be a grey area vis-a vis UNCLOS. I have the impression (shared by many like Byron Sequiera of the Daily Guardian) that such grey areas can turn into opportunistic green areas in international litigations or arbitrations, and no opportunity should be missed in plugging the loopholes. A positive fallout of this case is the recent insistence on following colour code for all fishing vessels.

- The Enrica Lexie incident has thrown open a unique chance to examine the legislational vulnerability of tropical fishing nations – where fishing is dominated by vessels under 20 m length – vis-a-vis human rights issues at sea.

- In an Actor-Network Theory (ANT) perspective. Thank You Latour. Engagement with the legal/legislative realm is unique to marine fisheries innovation system, unlike in agriculture.

- Echoing the sentiments of Vivek Katju (6 July 2020, The Hindu). Without eliminating the probable abuse of the immunity argument – likely to be quoted as a precedent – no discourse on human rights violations in the seascape will be meaningful.

Dr C Ramachandran is Principal Scientist, Division of Socio Economic Evaluation and Technology Transfer, ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Kochi, Kerala (ramchandrancnair@gmail.com)

Dr C Ramachandran is Principal Scientist, Division of Socio Economic Evaluation and Technology Transfer, ICAR-Central Marine Fisheries Research Institute (CMFRI), Kochi, Kerala (ramchandrancnair@gmail.com)

Disclaimer: The author’s perspectives are his own and are not to be considered as endorsed by the organisation he belongs to.

Dear Dr Rasheed,

This was a brilliant blog on a very important issue. Like, agriculture, fisheries is addressing the issues of the small-scale enterprises. Small-scale fisheries in India needs a definition so that welfare programmes may have a targeted approach. Otherwise, all benefits, of even the present programmes, may go to large fishers.

Poverty and environment are two big issues that had sustained the rich for a long time, and this has to alter.

Regards

S. N. Ojha

I congratulate Dr.C.Ramachandran for coming out with a very good blog on human rights issue of fishers. I was enriched by the vast information provided by him on various legal issues pertaining to fishers. I appreciate his concern for the fishers that too small fishers.There are several instances where we failed to bring the culprits to book. The famous one is the Bhopal Gas tragedy which claimed thousands of lives. Even after three and a half decades the survivors are yet to be compensated. The comments of Rachna Dhingra of Bhopal Group for Information and Action showed the lethargic way the law takes its course when such instances occur.

“In the last 35 years, the US government has sheltered the fugitives from the criminal case on the disaster and refused to pay heed to the concerns of the survivors. The US government continues to violate the Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty with India and is protecting Dow Chemical from being summoned before the Bhopal district court. International organisations such as the UN and WHO, that rush to help in cases of natural disasters, have hardly moved a finger in the case of the ongoing man-made disaster in Bhopal,” said (https://www.news18.com/news/india/compensation-clean-up-punishment-survivors-of-bhopal-gas-leak-have-the-same).

Whether it is natural or manmade the justice is very much delayed and it could well be considered as denied. Even in the case of Jelastine and Pink, the criminals were let off the hook with a paltry compensation of Rs10 crores. As the author pointed out the international legal community has to allay the concerns of a fisher when he asks “What is the guarantee that I will not be shot dead while I do legitimate fishing in our own waters?”.

Thanks to Dr.Rasheed Sulaiman V for encouraging Dr.Ramachandran to pen this blog and also to post it in the AESA site.