In this blog, Dr R M Prasad argues for taking urgent steps in India to support agriculture as the lockdown imposed to combat the COVID-19 pandemic disrupts agricultural value chains.

CONTEXT

The full impact of the coronavirus on food security and agricultural food systems globally is not yet known, which will unravel as the spread of the virus continues to evolve differently in different countries. But, it is evident that the impact of movement restrictions and disease containment efforts are negatively affecting all in the food supply chain, from producers to processors, marketers, transporters and consumers.

Impact on production and marketing

In India, the impact is felt at both the supply and demand sides. On the supply side, though there is no supply shock felt in terms of availability, restrictions on the movement of food has already slowed arrival of agricultural commodities in major markets. The transport restrictions and quarantine measures impede farmers’ access to input and output markets, curb productive capacities and increase risks of post-harvest losses. Increased levels of food loss and wastage are being witnessed in the supply of perishable commodities like fruits and vegetables.

At the consumer end, the food market is witnessing increased demand in both staple and ready-to-eat food that can be stored with a similar trend seen on e-commerce platforms. These trends make it difficult to sell fresh produce and increase loss of perishable produce, particularly vegetables and fish leading to income loss. Media reports indicate that the closure of hotels and restaurants during the lockdown has already reduced sale of milk and milk products. Fishers are badly affected due to lack of refrigeration, marketing and logistic support. Poultry farmers are also badly hit due to misinformation, particularly on social media, about chicken being carriers of coronavirus.

Impact on farm labour

The lockdown has come at a hard time as India’s peak farm activity occurs between April and June. This is when winter crops are harvested and sold, and is also the peak season for fruits. It is when farmers start sowing the rain-fed crops. The shortages of labour disrupts production and processing of food, mainly that of labour-intensive crops.

The migrant seasonal workers constitute 27% of the agricultural working force. Their services in farming in Punjab, Haryana, Telangana, Maharashtra and other states is significant. The workforce mainly hails from eastern Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and parts of Madhya Pradesh. In the present situation, this workforce cannot move through villages to reach the states where they work. Entry points are blocked to stop movement for fear of COVID-19. Media reports indicate that many labourers are either staying home or leaving for their hometown, fearing police action. In West Bengal, it is reported that most of the labourers hailing from Bihar and Jharkhand have returned to their hometowns fearing coronavirus.

EVERYTHING CAN WAIT, BUT NOT AGRICULTURE

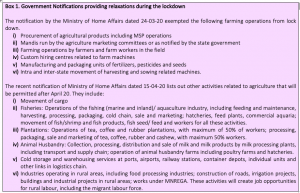

The general feeling is that the Centre should have created conditions for farmers to continue farm activities and should have calibrated the lockdown in such a way that the supply chain, from the farmer to the market, was cared for. Unfortunately, this did not happen. The government could have allowed flow of goods and the supply chain to continue taking safety measures in rural areas. The government only granted exemptions and relaxations for agriculture and allied sectors after a lapse of time (Box 1) by when some losses had already occurred.

ICAR has also issued an agro-advisory to maintain hygiene and social distancing by instructing farmers to take general precautions and safety measures during harvesting, post-harvest operations, storage and marketing of rabi crops. KVKs have translated these advisories in local languages and are disseminating them through ICTs.

APEDA has now resolved various issues related to transport, curfew passes and packaging units. Indian Railways introduced 67 routes for running 236 parcel specials to facilitate farmers, FPOs and traders for continuity of supply chain across the country.

Addressing the problem of marketing

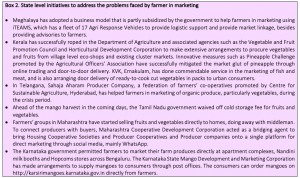

The main problem with farmers is that they are unable to sell their produce, which is a distribution nightmare on a national scale. However, some state governments have adopted certain measures for marketing of farm produce (Box 2).

Public procurement and social distancing

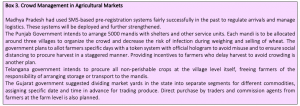

April-May is the period when wheat procurement starts in India. With COVID-19, the need to streamline and manage the flow of arrivals into mandis and procurement centres in line with protocols for social distancing is a big challenge. The mandis usually witness large crowds of farmers, which can undo all efforts at social distancing. Various governments have suggested measures to minimise crowding and contact (Box 3).

WAY FORWARD

- Strengthen local food systems: The period of social distancing and border closures may be an opportune time to strengthen local food systems, reducing the distance between production and consumption, wherever feasible. This will also help in reducing food miles. Food security policy and research should focus on a resilient society in which the population is able to fend for itself. Community-oriented activities like community gardens, community markets, community kitchen, etc. need to be promoted as a part of strengthening local food production system. Urban and peri-urban farming can be promoted. PRIs may plan for local governance of food systems in the country.

- Linking producers with consumers: Securing good quality food in sufficient quantities starts with an integrated food system–from production, distribution and processing to consumers. Such a food system can function effectively only with sufficient knowledge about all the stages and inter-system linkages. Traditionally, the focus on food security is on linking production with distribution and processing industries, and less on retailers and consumers, which needs to change. In this respect, there is a need to strengthen village markets. In place of malls in urban areas, malls in rural areas may be set up to sell fresh and processed produce of farmers.

- Strengthen decentralized procurement: It is time to devise policy measures about how we can support and protect our vast, interconnected agricultural production with a marketing system that is fair and safe, particularly during crisis situations. There is a need for establishing more collection and procurement centres at village level in place of centralized procurement. FPOs have to be strengthened and policy guidelines for retail marketing of farm produce have to be developed. Small poultry and dairy farmers, and fishers, need more targeted support as their pandemic-related input supply and market access problems warrant attention.

- Strengthen public and private transport of agricultural produce: There is a need for focus on both public and private food distribution systems to ensure that they work as equitably as possible. Transportation networks should be enabled for timely and safe movement of food. A significant proportion of agricultural produce, especially fresh produce, moves locally and regionally every day through public transport. If these systems remain closed for long (as is the case due to COVID-19), alternative transport has to be made available. The scope and potential of private transport services for movement of farm produce have to be explored.

- Promote future markets: Without appropriate market linkage, farmers fear losses due to poor market access. Futures markets need to be developed to serve as an alternative marketing channel for farmers, linking them to exchanges through FPOs. With an online marketing platform, the agricultural produce can also be traded at a location or with a buyer of choice. Electronic Warehouse Receipts (eNWRs) can break barriers and promote a national market in agricultural goods for the benefit of farmers. Farmers may be encouraged to use e-NAM facilities and hedge through futures and increased use of warehouse receipts.

- Safety nets and support for intermediaries in the agricultural value chain: The governments of Minnesota and Vermont in the United States have classified grocery clerks as “emergency workers”, entitling them to state-funded childcare services and other benefits so that they can continue to serve in stores. It is time to think about our own vast, largely informal networks of traders, wholesalers and retailers, and take concrete steps to support them as they keep working during shutdowns. Safety nets and support mechanisms for them have to be formulated.

- Strengthen direct cash transfer: Existing policy measures to ensure income and credit flows such as direct procurement, direct cash transfers to farmers as well as landless labourers and interest subvention through cash transfers may be strengthened. The direct income support under the Prime Minister Kisan Nidhi scheme may be given to farmers in toto at the earliest, instead of three instalments.

- Promote mechanisation in farming. This is important as labour supply is an important impediment in production. Harvesting is almost 80 percent mechanised in Punjab and Haryana. These states have fairly succeeded while other states face problems due to labour shortage during the crisis situation. There is a need to encourage adoption of small farm machineries by our farmers for which a well-defined strategy has to be developed.

- Strengthen MGNREGA: Labourers returning to villages due to lockdown can cause a sudden rise in rural unemployment levels. As a safety net, MGNREGA guidelines have to be modified and permission given to use the programme’s labour in farm related marketing activities. The huge number of migrants that have returned home due to lockdown (resulting in reverse migration) should also be provided opportunities to work as labourers under MGNREGA.

- Strengthen capacities of Extension and Advisory Services (EAS): Though the extension system has taken many pro-active measures to help farmers, there is a need for more involvement and formulation of innovative practices to enable them to address marketing challenges. Organizing capacity development programmes for extension personnel and farmers to empower them to overcome challenges can be taken up.

Selected References

Business Today, Coronavirus outbreak: Govt grants lockdown relaxations for agriculture, farming sectors, April 4, 2020.

FAO, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) – Addressing the impacts of COVID-19 in food crises, 7th April, 2020.

Gopinath Vrinda, ‘Food today, no farmer tomorrow’: Scientist Devinder Sharma on why there can be no agriculture lockdown, newslaundry.com, April 9, 2020.

Krishnamurthy Mekhala, Coronavirus pandemic is ominous news for India’s rabi crops and farm-to-food chain, The Print, March 25, 2020.

Prabhash K Dutta, Coronavirus makes India wake up to its migrant labourers, India Today March 30, 2020.

Sainath P, Coronavirus: How has the national lockdown affected rural India, India Today TV discussion, April 10, 2020.

Shekhar Singh Indra, Agriculture in the time of Covid-19, The Hindu Business Line, April 3, 2020.

Dr R M Prasad is a retired Faculty from Kerala Agricultural University, who had served in KHDP and KMIP (EU funded projects in Kerala), NIRD, Hyderabad and Government of Meghalaya. Presently, he is the Vice President of Farm Care Foundation, Thrissur, Kerala (email: drrmprasad@gmail.com)

“I congratulate Dr.RM Prasad for presenting a possible impact of COVID19 on food systems and also for giving several ideas to mitigate the impact with several successful models. Kerala is in an advantageous position in reducing the impact by virtue of its experience in dealing with Nipah virus. I agree with the author that it is better to encourage local food systems to maintain social distance. This is successfully being done by Paani foundation in Satara district of Maharashtra state (Vegetable distribution, NDTV.com 19th April). Several models are being tried by different agencies in various parts of the country. To deal with challenge posed by COVID 19 requires pooling the available ideas, evaluating them and take an appropriate decision to suite to the existing situation. It all depends up on the ingenuity of the masters of various departments in coming out with innovations to deal with the emerging situations with unified vision of helping the society at large”