Extension post-graduates in general and agricultural graduates in particular, face several challenges in competing with other development graduates and post-graduates in the job market. In this blog, Dr. Sagar Kisan Wadkar, explores the reasons behind this challenge by drawing lessons from courses in the development stream and suggests ways to address the lack of development perspectives in agricultural extension course curricula.

CHANGING CONTEXT OF AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT

Development is what those who are working for the betterment of people aim for. While at the global level, everyone is trying hard to achieve the UN’s “Global Agenda of 2030” i.e., Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), at the national level, there is an increasing focus on achieving the national agenda of “New Rural India – Doubling Farmers’ Income by 2022”. This calls for collective action with a common purpose by agencies, having different responsibilities and diverse capabilities that are essential for achieving sustainable growth (Wadkar, 2017).

In rural India agriculture is the main lifeline for transforming the rural economy. However, the agricultural sector faces several unprecedented challenges, especially those related to high price volatility, climate risks, and debt. Since majority of farmers (86%) are small and marginal with declining and fragmented landholdings, they are more vulnerable and risk prone to any type of uncertainty. Moreover, addressing many of these new challenges calls for collective action by farmers and collaboration among different agencies.

NEW ROLES FOR EXTENSION

Consequently, the demands placed on agricultural extension services have also increased manifold. As the extension system has a crucial role in strengthening and promoting sustainable agricultural practices as well as in enhancing food security and farm income, it needs to enhance its capacities to deal with these new challenges. However, the current course curricula used in extension teaching at the different levels (UG, PG and PhD) in Indian Universities are not supporting students to acquire the necessary competencies to address these types of challenges. Lack of development orientation in the curricula and continued dependence on traditional teaching methods are adversely affecting the job prospects of agriculture graduates and extension post-graduates in the development sector as they face tough competition from graduates and post-graduates from the development stream. More than a decade back, Leeuwis (2004) pointed that there is a need to reinvent agricultural extension as a professional practice, if it has to remain valid in the changing scenario (Box 1). Since the last two decades, many have been talking about identifying and strengthening core competencies among extension professionals (GFRAS 2012, 2015; Sulaiman et al. 2017). Many have also highlighted the need for revising extension curricula (Sulaiman 1996; Sulaiman and Van den Ban 2000; Acker and Grieshop 2004) and instructional methods (Chander2017). The need for redefining the role of social sciences in NARS in general, and agricultural extension scientists in particular, has also been highlighted (NAAS 2015).

| Box 1: Changes required for professional extension practice

The valid and relevant changes that may be required in this changing scenario are as follows: 1. Dealing with collective issues: Management of collective natural resources, chain management, collective input supply and marketing, organization building, multi-functional agriculture and linking farmers to market, value addition, etc. Source: Leeuwis with van den Ban (2004) |

Apart from all these aspects, extension organizations need to formulate a convergence mechanism whereby all relevant stakeholders could come together on one platform to serve people effectively and efficiently. Additionally, students need to acquire a development orientation along with hands-on training in order to build practical skills – to compete with other development graduates.

This would require.

a. Better understanding of rural livelihoods;

b. New and relevant competencies;

c. A wider choice of instructional methods that will help in acquiring these competencies.

These are discussed in detail below.

Understanding rural livelihoods

The main aim of ‘Extension education’ is to assist rural communities in gaining better livelihoods, improved lifestyles, and foster their welfare. Hence, the first and foremost responsibility of extension professionals is to strengthen and promote sustainable livelihood opportunities for their targeted clientele. Livelihood development is indispensable for eradicating all forms of poverty and to achieve food and nutritional security.

| Box 2: Strengthening rural livelihoods ’Livelihood’ is about ‘the means of gaining a living’ (Chambers 1995) and ‘a combination of the resources used and the activities undertaken (both on and off-farm) in order to live’ (DFID 2001). These means and/or combination of activities undertaken lead to diversified outcomes, and hence, how these activities/strategies affect livelihood pathways or trajectories is an important concern for livelihoods analysis. Thus extension professionals have to understand these perspectives while strategizing sustainable livelihood opportunities for rural people while also keeping in mind their means and resources. There are two broad approaches to livelihoods, which build on the strength of the rural poor viz., the narrower and the holistic views. The former deals with an economic focus on production, employment and household income, while the latter lays emphasis on the concepts of economic development, vulnerability, and environmental sustainability (Shackleton et al. 2000).Thus, farmers’ socio-economic and bio-physical characteristics, vulnerability context,institutional mechanism, along with the policies and the linkages between rural and urban areas, go into formulating their livelihood strategies. As a result there are differences in interpretation and variations in the livelihood approach, but they all have a common theoretical background, which includes Integrated Rural Development Planning (IRDP) approaches in the 1960s and 1970s; Farming System Research during the 1980s; Rapid Rural Appraisal (RRA); Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA); Participatory Action and Learning (PLA); Agro-Ecosystem Analysis; Political Ecology; Sustainability and Resilience Studies, etc. |

Globally, there are four prominent approaches that underline the sustainable livelihood framework and espouse its principles:

- Sustainable Livelihood Framework by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) ;

- Household Livelihood Security Approach by the Cooperative for Assistance and Relief (CARE, International NGOs);

- Oxford Committee for Famine Relief (Oxfam) – Sustainable Livelihood Approach;

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) – Sustainable Livelihood Approach.

These approach enables us to: a) Identify people’s resources/assets, sources of livelihood and what they are already doing to cope with risk and uncertainty; b) Explore the factors that constrain or enhance their livelihoods, and its linkages on the one hand, and policies, processes and institutions in the wider environment; and c) Identify appropriate measures that can strengthen assets, enhance capabilities, and reduce vulnerability. Therefore, the extension professional must know the concept of (sustainable) livelihoods and its components to understand farmers and their environment more competently.

New and relevant competencies

To become good development practitioner-cum-extension professionals, one should have the following competencies:

- Understanding of Self: to reflect on one’s own personality and belief systems as well as one’s emotional intelligence;

- Communication Skills: counseling, critical thinking, and negotiations, designing media-mix IEC (Information, Education & Communication) strategy for development;

- Group Behaviour and Dynamics: power and influence in groups, group decision making, conflict management; understanding leadership and its role in bringing out positive social change, problem solving skills, etc.

- Facilitation of Social Capital: ways to approach villagers, organize meetings and group discussions in the field/villages, sensitization and social mobilization of people, identification of felt & unfelt needs of farmers, group formation – need/interest-based groups to address common issues; selection of lead/progressive farmers, etc.

- Development Programme Planning and Management: project planning formulation and report writing, logical framework analysis, stakeholder analysis, policy-gap analysis, etc.

- Livelihood Management: development of backward-forward linkages, livelihood mapping, (social) entrepreneurship, market linkages, value addition, etc.

- Documentation and Data Analytics Skills: developing data collection tools and its administration, evidence-based research, participatory action research, good/best practice writing, qualitative & quantitative data analytics, etc.

The existing curricula used for teaching extension in India, at all levels, do not sufficiently prepare students in acquiring these competencies, due to which agri-graduates and extension professionals often fail while competing with other development graduates. There could be several reasons for this, but I would like to highlight four, which I consider important.

- Lack of development orientation and guidance on future prospects;

- Lack of field exposure and practical skills;

- Lack of content and methodology to understand and deal with contemporary issues;

- Traditional teaching methodologies.

It is time that extension faculty in universities learn how teaching is organized in development courses offered by other universities/institutions. Given below is the experience from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), and I hope some of these experiences might be useful in the context of extension curricula reform in India.

New ways of delivering content

Development Teaching at TISS:

The Tata Institute of Social Sciences is a unique institute of social sciences; it focuses on the humanistic aspects of social sciences that is blended with science to nurture imagination, creativity, and rigorous critical thought (Box 3). In general, with reference to agriculture development, it has courses, such as MA in Social Work in Community Organization & Development Practice, Master’s in Social Work in Livelihoods and Entrepreneurship, MA in HRM & Labour Relations, MA in Social Entrepreneurship, MA in Development Studies, MA in Women’s Studies, MA/MSc in Climate Change and Sustainability– where students are trained and nurtured to understand the nuances of development.

The Tata Institute of Social Sciences is a unique institute of social sciences; it focuses on the humanistic aspects of social sciences that is blended with science to nurture imagination, creativity, and rigorous critical thought (Box 3). In general, with reference to agriculture development, it has courses, such as MA in Social Work in Community Organization & Development Practice, Master’s in Social Work in Livelihoods and Entrepreneurship, MA in HRM & Labour Relations, MA in Social Entrepreneurship, MA in Development Studies, MA in Women’s Studies, MA/MSc in Climate Change and Sustainability– where students are trained and nurtured to understand the nuances of development.

| Box 3: Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS) TISS has 45 centres across 21 schools, and 8 independent centers spread across four campuses (Guwahati, Hyderabad, Mumbai, and Tuljapur) and offers a number of BA, MA/ MSc, MPhil and PhD courses related to social sciences and rural development, such as education, (public) health studies, development studies, habitat studies, management & labour studies, media & cultural studies, disaster studies, public policy & governance, livelihoods & development, gender studies, human ecology; laws, rights and constitutional governance, etc. All programmes attempt to build skills in facilitating change and transformation in rural areas at the level of individuals, groups and communities. Students are exposed to multiple pedagogies of teaching and learning with a strong emphasis on exposure to engagement, along with guided mentoring by the faculty and field-based organisations, together with group-based experiential learning. It also endeavours to strengthen the capacities of students to develop appropriate skills and talents to make them committed and dedicated development professionals. |

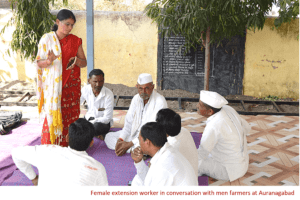

Instructional Methodologies: The teaching and academic programmes are well blended with field learning, supported and facilitated by development partners and people’s institutions. Field learning activities not only help students to enhance their sensitivity to social realities, but also provide different lenses that enable them to see the linkages between theory and practice in a praxis mode. Diverse pedagogical methods, such as lecture-cum- discussion, case method, group work & presentation, simulation exercises, etc., are in use to enrich the entire learning process for both students and teachers.

- Lecture-cum-Discussion: It is a two-way process whereby a teacher and students learn from each other and share different perspectives on a particular issue/concept. Generally it is based on prior shared reading materials (articles, research studies and other relevant literature) as per course content.

- Case Method: It gives students the ability to quickly make sense of a complex problem, rapidly arrive at a reasonable solution, and communicate that solution to others in a succinct and effective manner. It provides a lively context, facilitates learning by having a professional dialogue between participants and thereby empowers students to reflect upon the peculiar demands of their profession.

Internship and Fieldwork: Internship and Fieldwork form an integral component of the course curriculum at both the Bachelor’s and Master’s levels of the academic programme.

Internship -These are 6-8week internships, where students are interned with various government, non-government, civil society or community organisations in all the major states of India. As per their course/degree programme most of the students focus on themes like rural livelihoods, forestry, water resources, human rights, entrepreneurship, delivery of social protection programmes, decentralised governance, including performance of Panchayats, etc., for their field work and internship. This learning help students in their overall learning process and in formulating their research dissertations/projects.

Fieldwork – is meant to translate knowledge and techniques learnt during the course into action for practical use. The basic purpose is to maintain equilibrium between the academic level of the students and their working capacities with clients. It is not merely visiting an agency or observing what goes on. It is done under the able supervision of a well-equipped faculty supervisor and also, sometimes, under an agency supervisor at particular field sites/agencies/organisations to coordinate a set of activities. The students are helped through supervision so as to enable them for working in a complex, intricate and composite social environment.

Marketing of the Programme and Students: TISS has a centralised placement cell, where a dedicated team use a multi-pronged approach to build a composite employability picture for each student by linking their aspirations/career expectations of relevant organisations. The cell also undertakes different career development sessions/tests comprising one-to-one counselling sessions, career identification exercises, competency mapping and development area identification, and career path planning to enhance and strengthen their personality.

IMPLICATIONS FOR EXTENSION PROFESSIONALS AND COURSE CURRICULA

There is an urgent need to redesign extension curricula to enable students to become very capable development professionals.

At the UG level, the main objective could be to enhance their practical extension-related skills, and acquire a development perspective; as well as to orient students on future prospects of the (extension) discipline so that they can make a choice-based selection of extension at the PG level.

At the PG levels, there should be core discipline courses + specialized modules/courses in one of the areas of the discipline (as per student’s interest and availability of expertise) along with Internship + Research/ Project. The PhD level training should be about further development of their field-based skills and critical and reflective understanding of the selected specialization. In addition, we should encourage students to take up field-based (participatory) action research.

Other specific suggestions include:

- Strengthening theoretical and practical skills related to socio-behavioral sciences: Extension education discipline is based on behavioral change communication and so the teaching should provide some basic grounding on psychology, sociology, social-psychology and anthropology. However, this aspect is neglected in the present curricula which are mainly theoretical, and thus lacking in relevant field extension practice.

- Introduce understanding of rural livelihood promotion: We often use livelihood interchangeably with agriculture, however, the livelihood concept is too broad and complex and the application of knowledge and technology is often constrained by socio-economic, institutional and policy challenges. In such a scenario, the livelihood analysis of any particular area/region helps us to understand these interlinked factors and accordingly an appropriate strategy can be developed. Therefore, these aspects of livelihoods need to be introduced in the extension course curricula.

- Strengthening process skills: There is a dire need to develop and strengthen the process skills of students from the perspective of peoples’ participation, design and action in development. This enables students to apply participatory approaches in evolving and strengthening community-based, people-centered development initiatives. In this context an ‘Institutional and stakeholder analysis’ is an essential part of any new planning and management initiative, especially where a greater degree of integration is sought. The nature and operation of institutions, and their mode of decision making, will have major implications for the implementation of any strategy or planning related to the promotion of sustainable development.

- Promote action research, especially at the PhD level: Being part of the social science discipline, there is a need to promote action research, which is a blend of theory and practice, which focuses on co-creation of knowledge of practice in the collaborative process of solving field problems, for the purpose of bringing change.

- Promote learning by doing: While we teach the importance of learning by doing, the same principle is seldom followed in extension teaching. There is need to lay more emphasis on strengthening practicals and field exposure in extension teaching.

END NOTE

The future of extension as a profession and a discipline depends on us. The process of change has to start with us. Waiting for committees which revisit extension curricula once in a decade is not going to help. We need collective action, starting with all of us to develop more appropriate content and relevant instructional methods; and I hope the recently formed MANAGE-University Alliance for strengthening extension and advisory services will take a lead in this direction. Let us make our discipline of extension more attractive in order to draw in the best talent; and let us devote ourselves to training and nurturing future extension professionals.

References

Acker, David and Grieshop, James. (2004.) University curricula in agricultural and extension education: An analysis of what we teach and what we publish. Journal of International Agricultural and Extension Education, 11(3):53-61.

Chambers, R. (1995.) Poverty and livelihoods: Whose reality counts? ID discussion paper, 347. Brighton: IDS. http://www.archidev.org/IMG/pdf/p173.pdf

Chander, M. (2017.) Teaching in agricultural extension education: Can we improve it? AESA Blog 67, March 2017. http://www.aesa-gfras.net/admin/kcfinder/upload/files/Blog%2067-MaheshFinal%283%29.pdf

DFID. (2001.) DFID sustainable livelihoods distance learning guide glossary. www.livelihoods.org

GFRAS. (2012.) The New Extensionist: Roles, Strategies, and Capacities to Strengthen Extension and Advisory Services. Global Forum for Rural Advisory Services, Switzerland. http://www.gfras.org/en/knowledge/gfraspublications.html?download=126:the-new-extensionist-positionpaper

GFRAS. (2015.) The New Extensionist: Core competencies for individuals, Global Forum for Rural Advisory Services, Switzerland. http://www.g-fras.org/en/knowledge/gfraspublications.html?download=358:the-newextensionist- ore-competencies-for-individuals

Leeuwis, Cees. (2004.) Communication for rural innovation: Rethinking Agricultural extension. Blackwell Science Ltd. http://www.modares.ac.ir/uploads/Agr. Oth.Lib.8.pdf

NAAS. (2015.) Role of social scientists in National Agricultural Research System (NARS). Status/Strategy Paper 1.New Delhi: National Academy of Agricultural Sciences. P. 16. https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B2ESp7vQtAoZVnhYNXFkWUNPcEk/view

Shackleton, S., Shackleton, C. and Cousins, D. (2000.) The economic value of land and natural resources to rural livelihoods: Case studies from South Africa. In: At the crossroads: Land and agrarian reform in South Africa into the 21st century, edited by Ben Cousins. Cape Town and Johannesburg: Programme for Land and Agrarian Studies, University of the Western Cape and National Land Committee.

Sulaiman Umar, Norsida Man, Nolila Mohd Nawi, Ismail Abd. Latif, and Bahaman Abu Samah. (2017.) Core competency requirements among extension workers in peninsular Malaysia: Use of Borich’s needs assessment model. Evaluation and Program Planning, 62:9-14. ISSN 0149-7189.

Sulaiman, R. V. and Anne W. Van den Ban. (2000.) Reorienting agricultural extension curricula in India. The Journal of Agricultural Education and Extension, 7(2):69-78.

Sulaiman, R. V. (1996.) Post-graduate curriculum in agricultural extension – A synthesis. In: S. Selvarajan and Sulaiman R. V. (Eds.) Workshop proceedings on social sciences education in agriculture: Perspective for future. New Delhi: National Institute of Agricultural Economics and Policy Research.

Wadkar, S. K. (2017.) Farmers’ collective action as a tool in promoting sustainable livelihood opportunities to achieve sustainable development goals. Poster presented at the National Conference on SDGs: India’s Preparedness and Role of Agriculture, organised by TAAS and IFPRI, 11-12 May 2017 at NASC Complex, New Delhi.

Dr. Sagar Kisan Wadkar is Assistant Professor-cum-Programme Coordinator at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, under the Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellows Scheme (PMRDFs). He earned his M.Sc. (Agricultural Extension & Communication) from G.B.P.U.A.&T., Pantnagar, Uttarakhand, and PhD (Agricultural Extension Education) from ICAR – National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana. (email: sagarkwadkar@gmail.com)

Dr. Sagar Kisan Wadkar is Assistant Professor-cum-Programme Coordinator at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), Mumbai, under the Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellows Scheme (PMRDFs). He earned his M.Sc. (Agricultural Extension & Communication) from G.B.P.U.A.&T., Pantnagar, Uttarakhand, and PhD (Agricultural Extension Education) from ICAR – National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal, Haryana. (email: sagarkwadkar@gmail.com)

“How the development is linked to extension is not clear to many of the extensionists as the concept of development is either missing on the curricula or not dealt with properly by the teachers. As pointed out by Dr.Sagar Kisan Wadkar, we need to change the curriculum and syllabus of extension courses and the teaching methodologies to impart the skills required by the students at graduate, pg and doctoral levels. This is necessary to enable the graduates and post graduates to face the present and future challenges in achieving sustainable livelihoods for the small holders and food security for the nation. Bringing changes in the curriculum alone is not sufficient as it needs to be properly taught. Many of us have seen how the internship programme or field extension programmes are being handled. I feel that the teachers have to play a major role in bringing about these changes and TISS modules offer lot of scope for us to learn especially the rural development concepts.

I reiterate his end note that “ the future of extension as a profession and a discipline depends on us. The process of change has to start with us” rather than waiting for others to bring in changes for us and for our discipline.

Congratulations to Dr.Sagar for coming out with a very useful blog and thanks to AESA for making it accessible to me”.